The Eight Forbidden Strikes of Praying Mantis Fist

八打八不打

In the Chinese Martial Art of Northern Praying Mantis, there exists a list of Eight Places to Strike on an opponent’s body if the objective is to merely injure them and end the fight. Paired along side these are another list: Eight Places Not to Strike. Hitting these points is considered lethal, and not to be performed unless under dire circumstances. While these lists could be translated a number of ways (e.g. Eight Allowable Targets, Eight Forbidden Targets) we will hereafter opt for the most literal in the interest of brevity: 8 Hits/8 No Hits (literally: 八打八不打).

1800’s

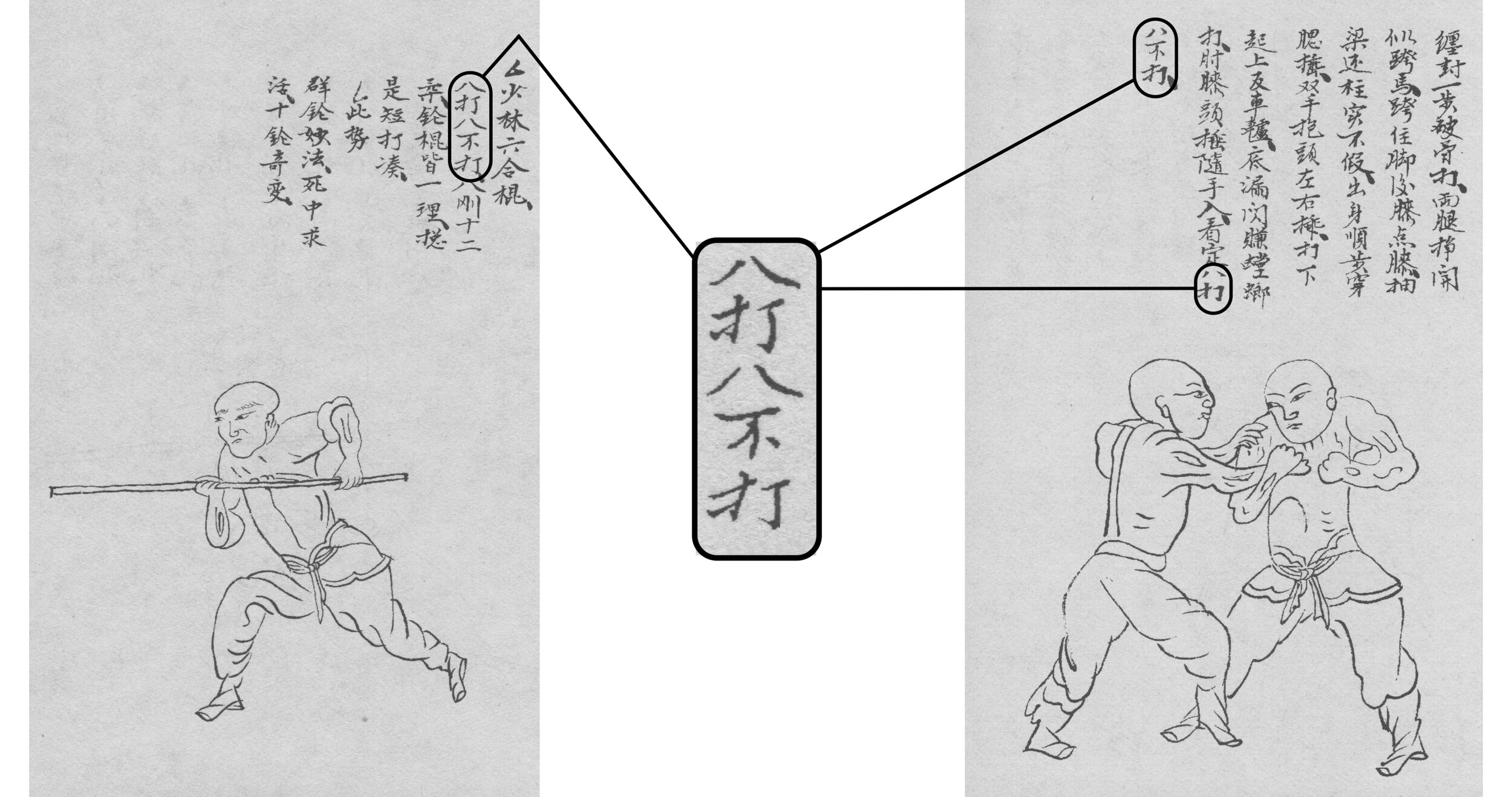

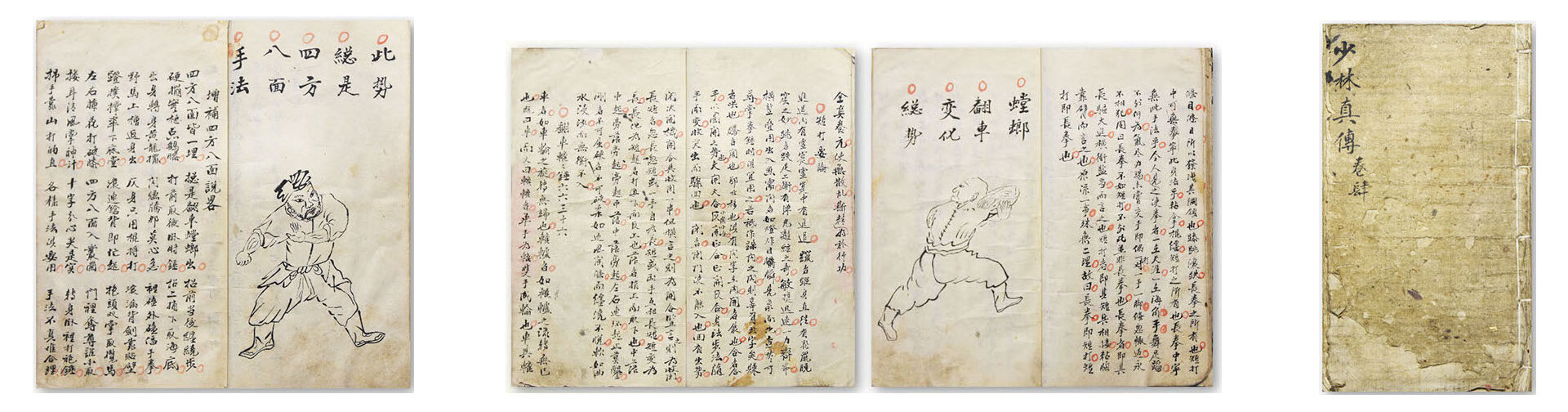

Mentions of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits are found in some of the oldest manuals associated with Mantis boxing: the Hui Xiang Luohan Duanda (繪像羅漢短打) and the Shaolin Yibo Zhenchuan (少林衣钵真传). For reference and sake of brevity, hereafter these manuals will be referred to as Short Strikes and Shaolin Authentics, respectively.

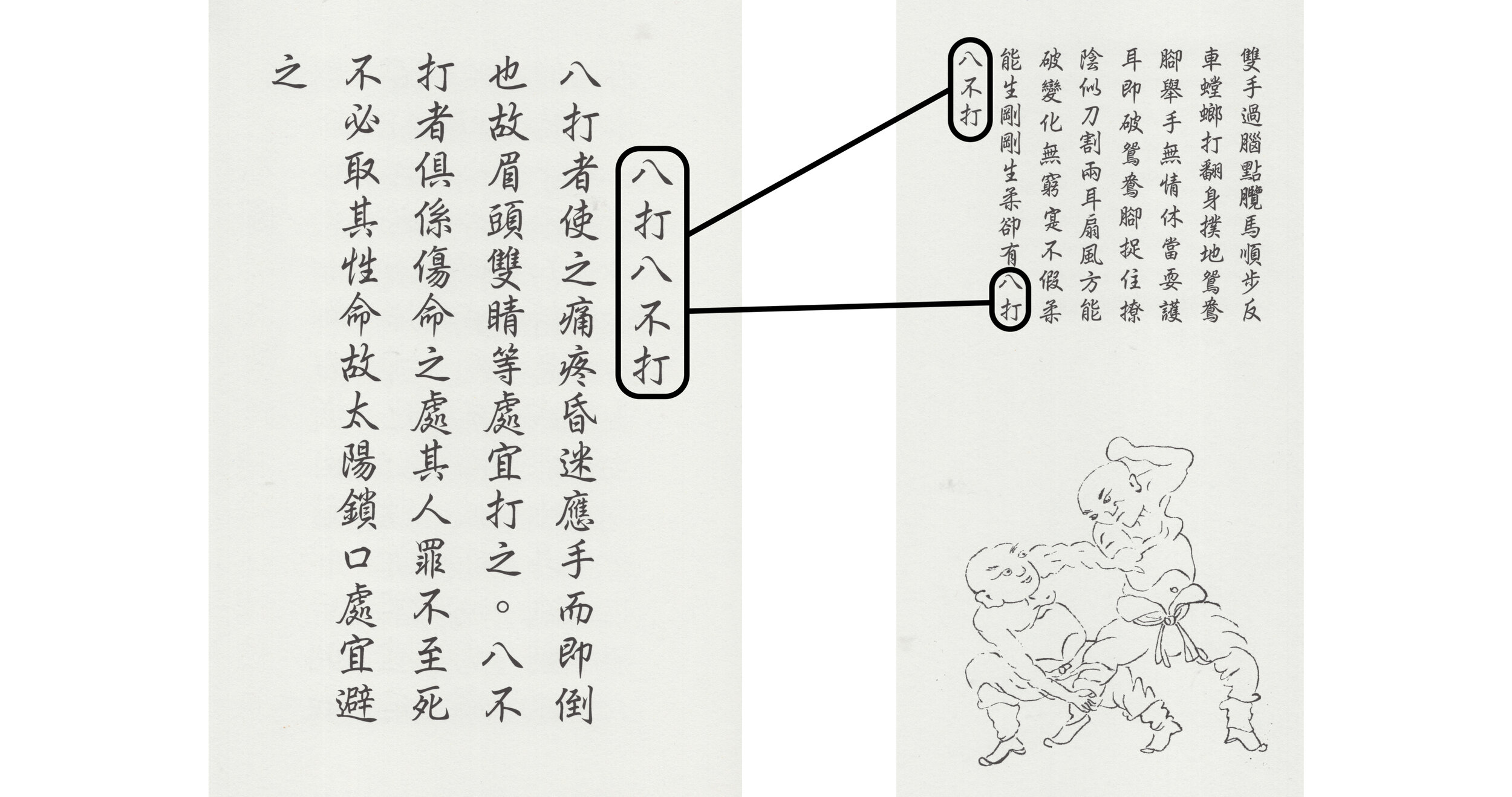

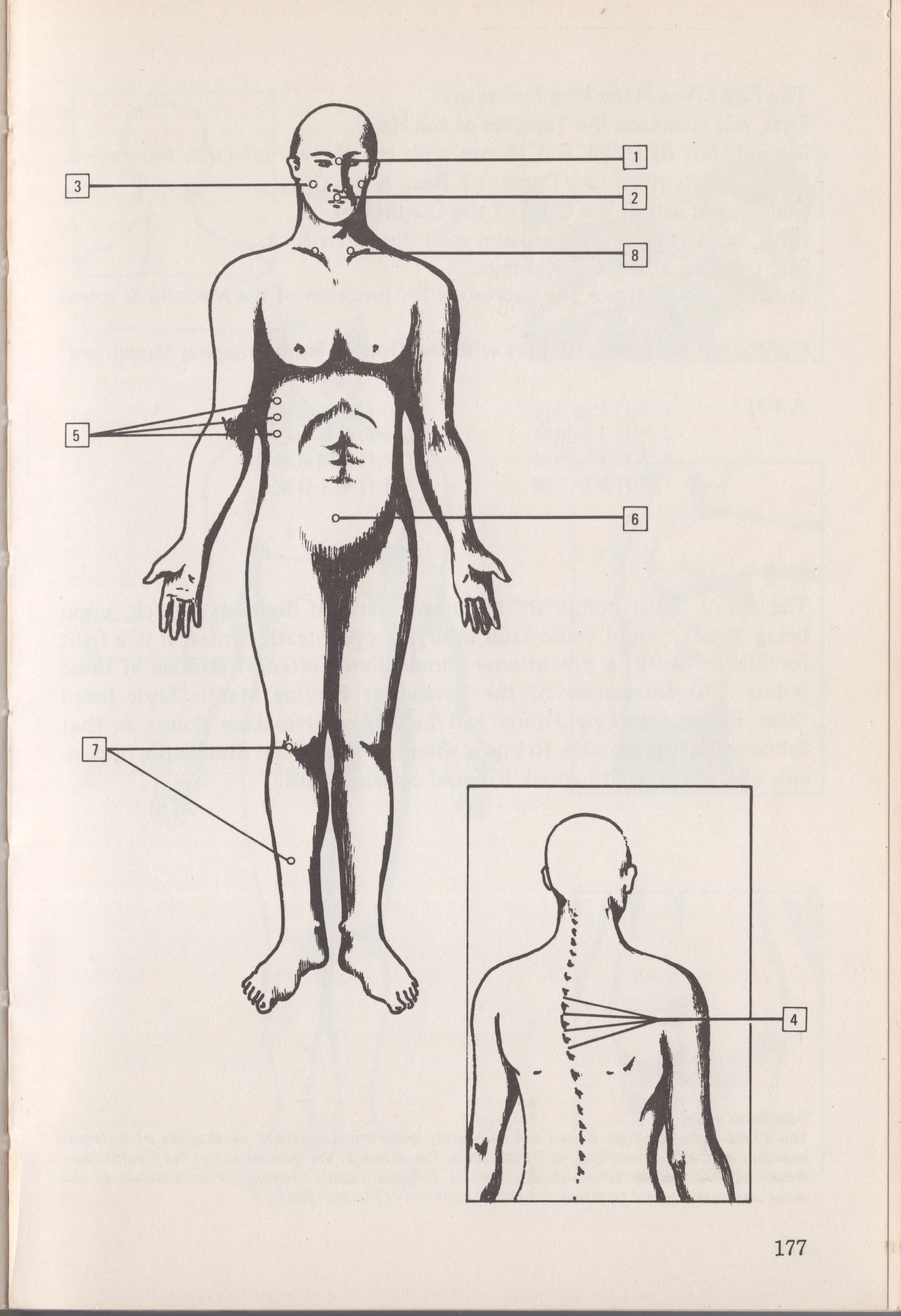

Above: All 16 locations of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits listed in the Shaolin Authentics.

Tradition ascribes the creation of these manuals (and thus, one of the earliest advocates for the 8 Hits/8 No Hits) to Shengxiao Daoren (升霄道人), a wondering daoist monk who was also a practitioner of Praying Mantis Fist. In reality, confirming beyond reasonable doubt who exactly composed each of these manuals, and in what year, remains difficult. A copy exists from the 1800’s, but is it possible these books originated even earlier in the 1700’s? While products of the Qing Dynasty, some of the ideas and techniques within the manual date back even further, as terms and allusions within the text itself reference the Ming dynasty hundreds of years prior. What seems certain is that Short Strikes was composed first and Shaolin Authentics later copied and expanded upon the original volume, adding material such as commentaries along with entirely new chapters. The 8 Hits/8 No Hits are present in both volumes.

Above: Two pages from the Shaolin Authentics that reference the 8 Hits/8 No Hits.

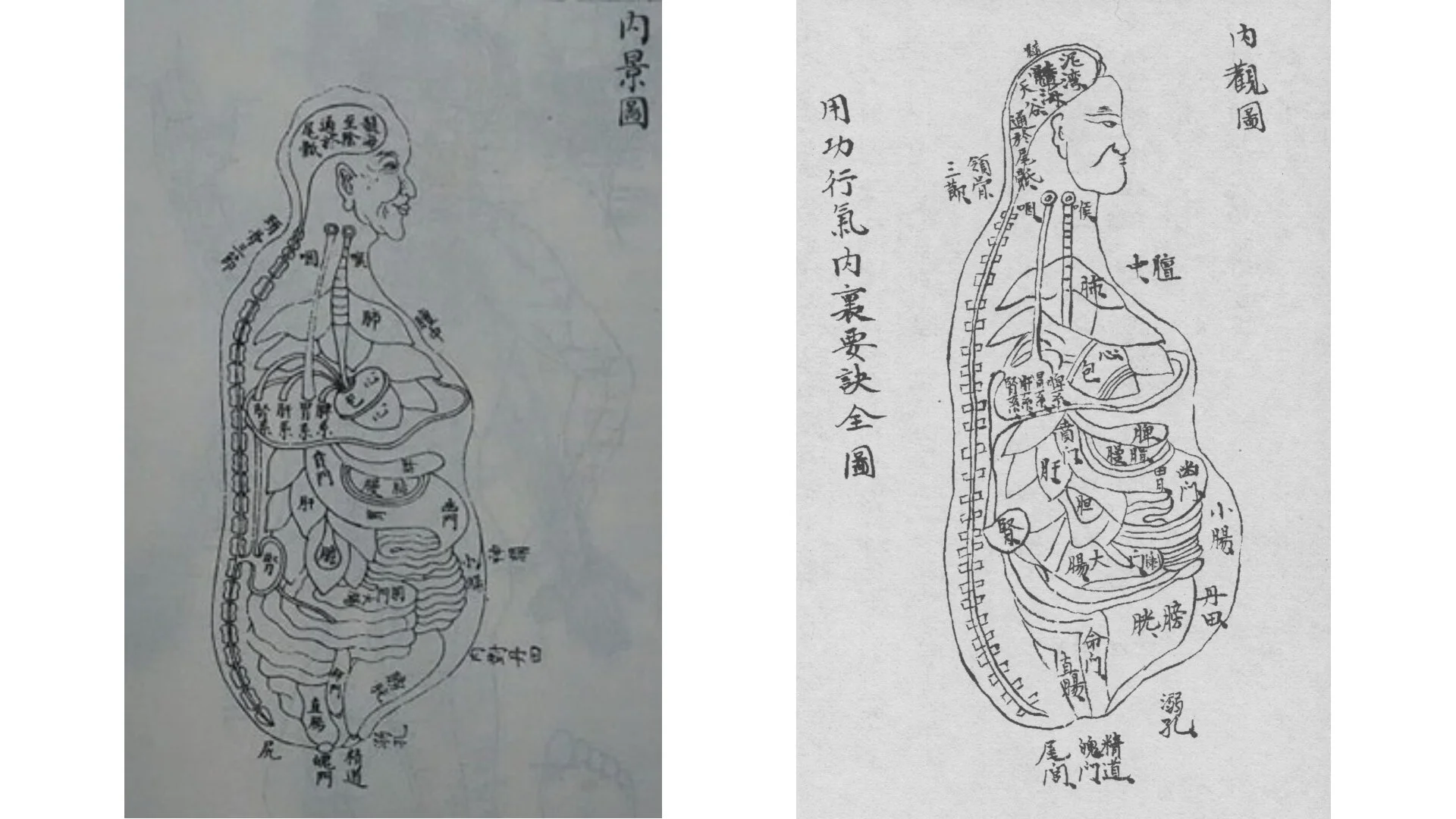

Right: From the Praying Mantis manual Shaolin Authentics: a hand-drawn diagram of the organs, some of which were targets of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits. Left: A Chinese woodcut illustration from a popular medicine book of the 1600’s, almost certainly the source from which the Mantis manual was copied. Just as modern day fighters consult with nutritionists and physicians, so too did Mantis boxers draw upon the medical resources and knowledge of their time to increase their fighting efficacy.[1]

Above: An appearance of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits in the Praying Mantis Short Strikes manual.

By the end of the 1800’s, one of the first recorded owners of the Shaolin Authentics manual arises in written history: Praying Mantis master Fan Xudong (范旭东). From his tournament fighting in Russia to his iron-palm skills and influential students, there is enough material to warrant an entire article dedicated to Fan Xudong. For now it is enough to note that a well-established Mantis master apparently possessed a copy of this manual and passed it on through his lineage. This was no doubt an influential moment for the survival and spread of the 8 Hit/8 No Hits Theory, as some of the students from Fan Xudong’s lineage would migrate from Northern China to Hong Kong, and eventually to America.

Seated Above: Praying Mantis master Fan Xudong (范旭东), unverified birth-date between 1840 and 1875, unverified death-date circa 1936. [2][3] Below: Fan Xudong’s personal copy of the Shaolin Authentics, listing within the 8 Hits/8 No Hits.

1900’s

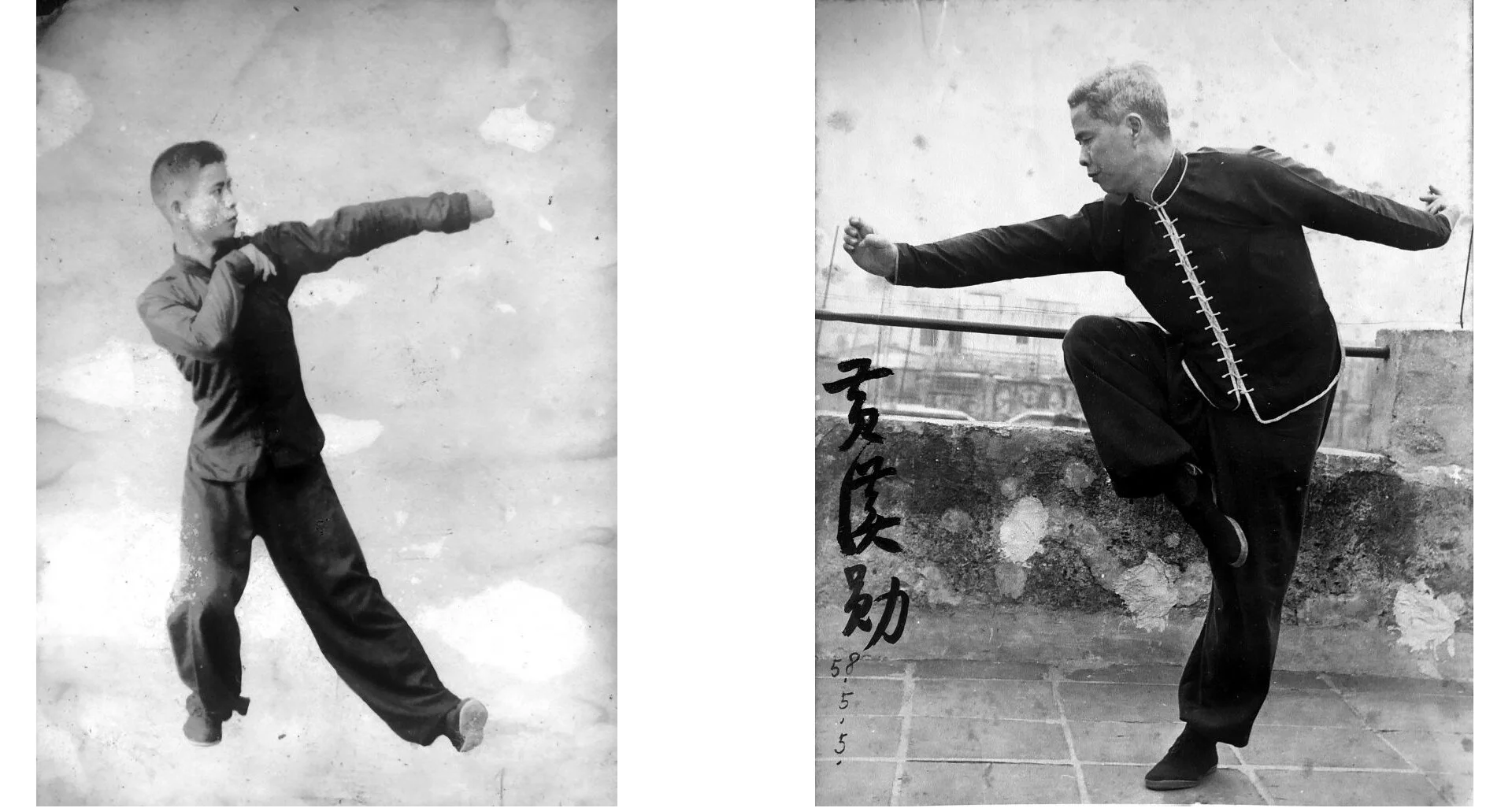

In 1919, one of Fan Xudong’s students, Luo Guangyu, would travel south and eventually train Wong Honfan (1915-1974), arguably the most influential Praying Mantis author to date. By the time he was 24, Wong Honfan had already copied the Shaolin Authentics by hand, and thus the list of 8 Hit/8 No Hits. While previously this list of targets on the human body had been secretive knowledge, passed down privately from master to disciple, Wong Honfan would go on to include the 8 Hits/8 Non Hits in his published books, marking one if the first times this list had been made public.

Left: A twenty-year old Wong Honfan performs a sweeping kick with a strike to the throat (雙刁左揪腿). Right: An older Wong Honfan on the rooftop of his school in Hong Kong. To this day Wong Honfan remains the most prolific author of Mantis Boxing to have lived. [5]

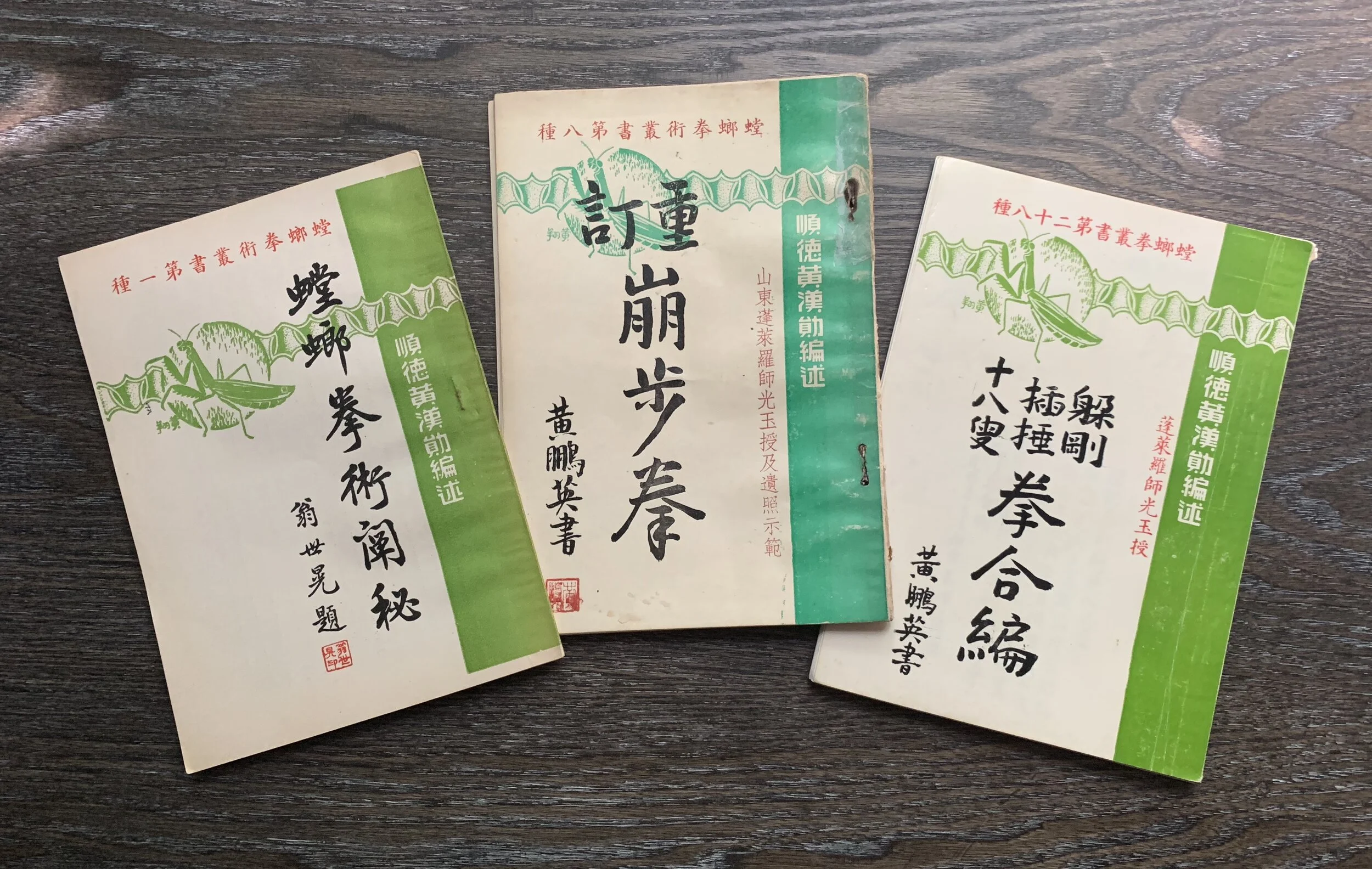

In 1946, the first book Wong Honfan would ever publish, Secrets of the Mantis Boxing Art (螳螂拳術闡秘) Vol. 1, contained an introduction to the 8 Hit/8 No Hits and their locations. Throughout his forty year career as a teacher, Wong Honfan would author many more books with references to the 8 Hit/8 No Hits sprinkled through out his works. The manuals he wrote were produced in extremely small quantities and with limited print runs; originally for his students, they were also enthusiastically embraced by the wider martial arts community.

Above: From the Ravenswood Academy Archives: Three of Wong Honfan’s Mantis manuals that make mention of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits. Volume One (far left) lists where to find all sixteen of these places on the human anatomy, while Volumes Eight and Twenty Eight mention the targets in relation to fighting applications. Full versions of these manuals can be viewed here: http://theravenswoodacademy.com/the-archive

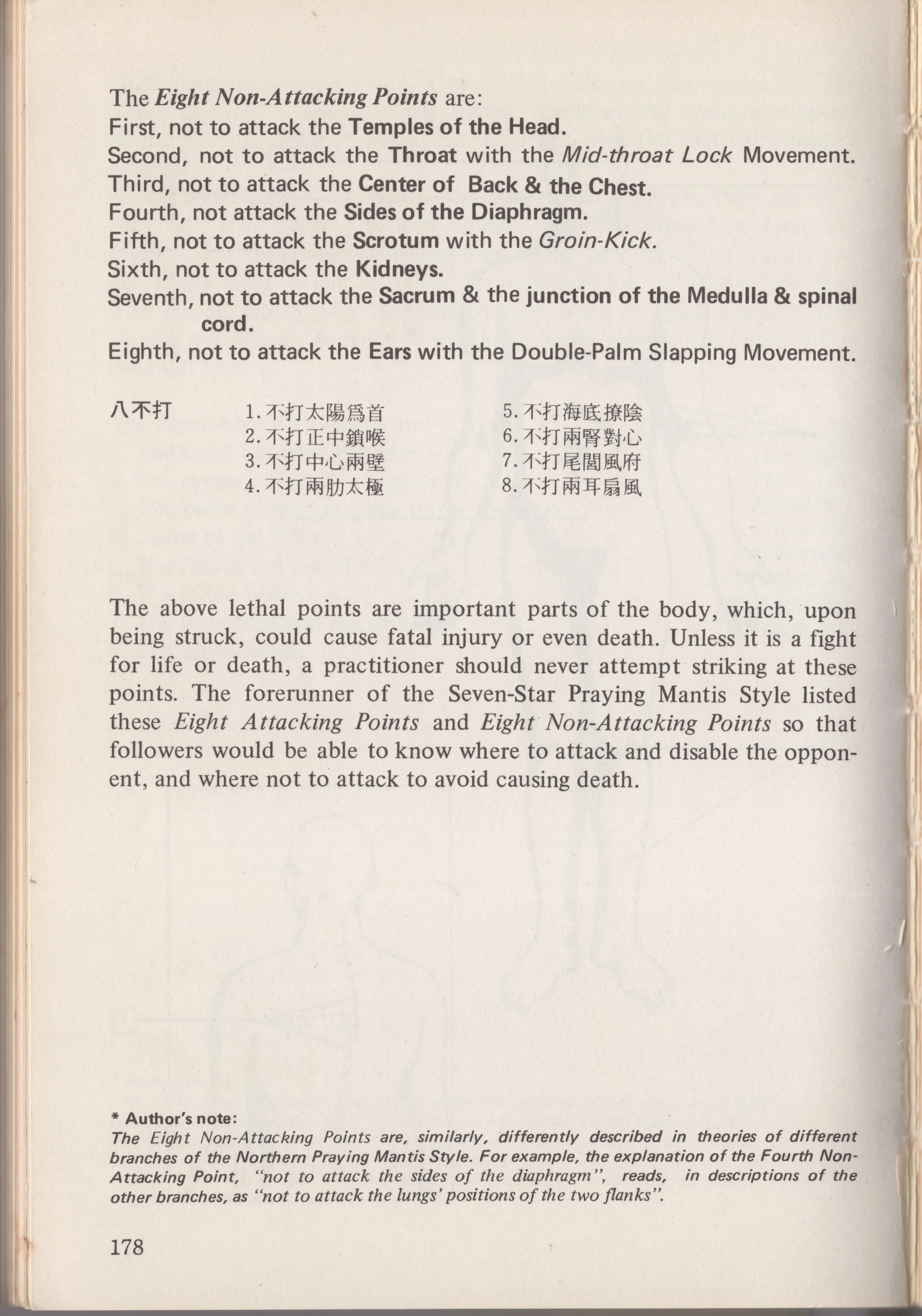

Above: Wong Honfan’s introduction and locations for the 8 Hit/8 No Hits. Below: The text translated by Paul Brennan, sourced from Brennan Translations.

From Wong Honfan’s Secrets of the Mantis Boxing Art 螳螂拳術闡秘, written in 1946 [4]:

八打

THE EIGHT ALLOWABLE TARGETS

每部位皆屬次要,雖不致命,亦必重傷,如遇强手,非此不足以致勝,然不可輕予施用,以傷好生之德,惟吾同道愼之。

These are all secondary targets. Although not life-threatening, they are sure to cause injury. If you encounter an attacker who is highly skilled, these will be sufficient to defeat him. But you must not employ them rashly or you may do injury to your own life-sparing virtue. I hope my fellow practitioners will be mindful.

(一打)眉頭雙睛

1. the space between the eyebrows as well as the eyes themselves

(二打)唇上人中

2. the Ren Zhong acupoint above the upper lip

(三打)穿腮耳門

3. the hollow between cheek and earlobe

(四打)背後骨縫

4. the spine

(五打)脅內肺腑

5. the lungs under the upper ribs

(六打)撩陰高骨

6. the pelvic bone

(七打)鶴膝虎頭

7. the soft tissue just below the kneecap

(八打)破骨千斤

8. the shins

八不打

THE EIGHT FORBIDDEN TARGETS

是皆致命之處,苟非性命相搏,幸毋施用,若對方不念人命之為重,亦祗招之而已。

All of these targets are for life-threatening situations [and are thus the primary targets]. If you are not fighting for your life, I hope you will not employ them. Only use them if your attacker clearly does not consider human life to be of any value.

(一不打)太陽為首

1. the temples

(二不打)正中鎖喉

2. the windpipe

(三不打)中心兩壁

3. the solar plexus

(四不打)兩肋太極

4. the false ribs

(五不打)海底撩陰

5. the groin

(六不打)兩腎對心

6. the kidneys

(七不打)尾閭風府

7. the tailbone

(八不打)两耳扇風

8. the ears

Above Middle Page: In Volume 11 detailing the two-person Beng-bu set, Wong Honfan mentions the 8 Hits/8 No Hits in passing, attributing their incorporation into the system directly to the legendary founder of Mantis Boxing, Wang Lang. In his own time, Wong Honfan considered Wang Lang to have existed about three hundred years prior.

Above: Accompanied by hundreds of photos, Wong Honfan’s work documented and described a great deal of techniques from the Praying Mantis School, some including applications specific to the 8 Hits/8 No Hits. Below: A portion of the text from the right image translated by Paul Brennan, sourced from Brennan Translations.

From page 31 of 重訂崩步拳 [Avalanche Steps Boxing Set (Revised)]:

肺腑乃八打之一… 改以反刁手之尖形,利其小而着力也。

“The organs lying behind the ribs are one of the ‘eight recommended targets’…employ the wrist strike of a reverse hooking hand in order to use the smallest amount of effort and yet get the greatest penetrative impact.” [4]

Above: Calligraphy by Wong Honfan espousing the theories of Praying Mantis (8 Hits/8 No Hits, 8 Hard, 12 Soft, etc.). Given to Brendan Lai in the early 1970’s, this work attests that from his books in the 1940’s all the way to the end of his life in 1974, Wong Honfan included the 8 Hits/8 No Hits as part of his curriculum. [6]

Enter the Dragon

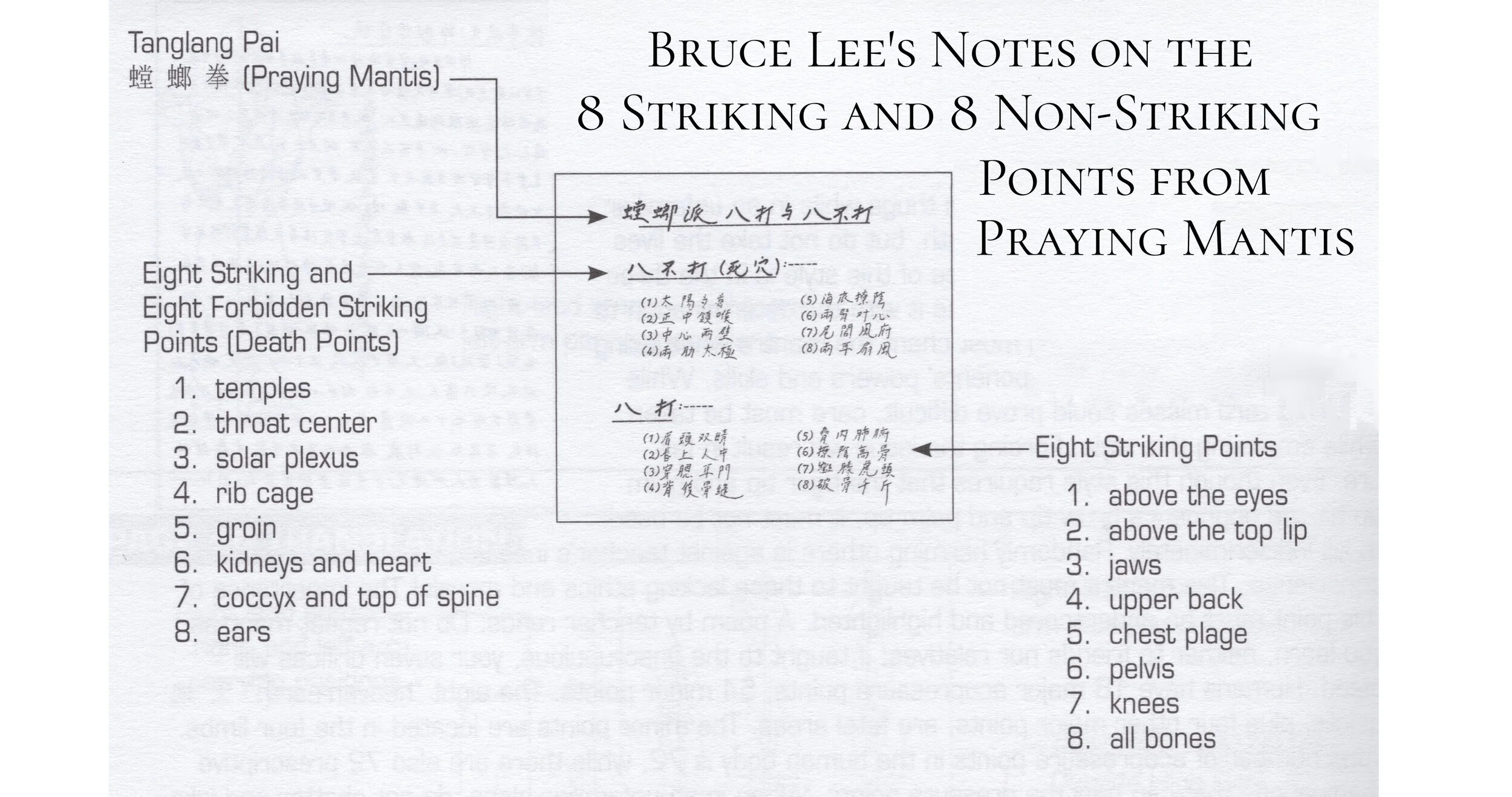

Undeniably, the most famous person to ever study the 8 Hits/8 No Hits from Wong Honfan’s Praying Mantis manuals was the martial artist and actor Bruce Lee.

Above: Bruce Lee had over a dozen of Wong Honfan’s Praying Mantis books which he studied, translated and gave to senior students. A forthcoming article will outline in detail Bruce Lee’s connection to Praying Mantis Kung Fu. [7]

We know that Bruce Lee had a copy of Wong Honfan’s Secrets of the Mantis Boxing Art, the same volume that lists the 8 Hit/8 No Hits. During his time studying philosophy at the University of Washington from 1961 to 1964, Bruce created a “Gung Fu” scrapbook with a cutout directly from the pages of Wong Honfan’s manual, placing the volume firmly in his collection. He also copied the list of 8 Hit/No Hits, character for character.

Above: Bruce Lee’s copy of Praying Mantis’ 8 Hits/8 No Hits, published posthumously in The Dao of Jeet Kune Do, 1975. Translation by Eric Chen.

Into the West: English Translations for the First Time

Barring the possibility of some obscure martial arts magazine article currently unknown to us, the very first time the 8 Hits/8 No Hits were widely published in the English language was in 1975 with the posthumous publication of Bruce Lee’s notes under the title The Tao of Jeet Kune Do.

Above: The 8 Hits/8 No Hits briefly mentioned in a 1973 copy of Black Belt Magazine. View the full article HERE

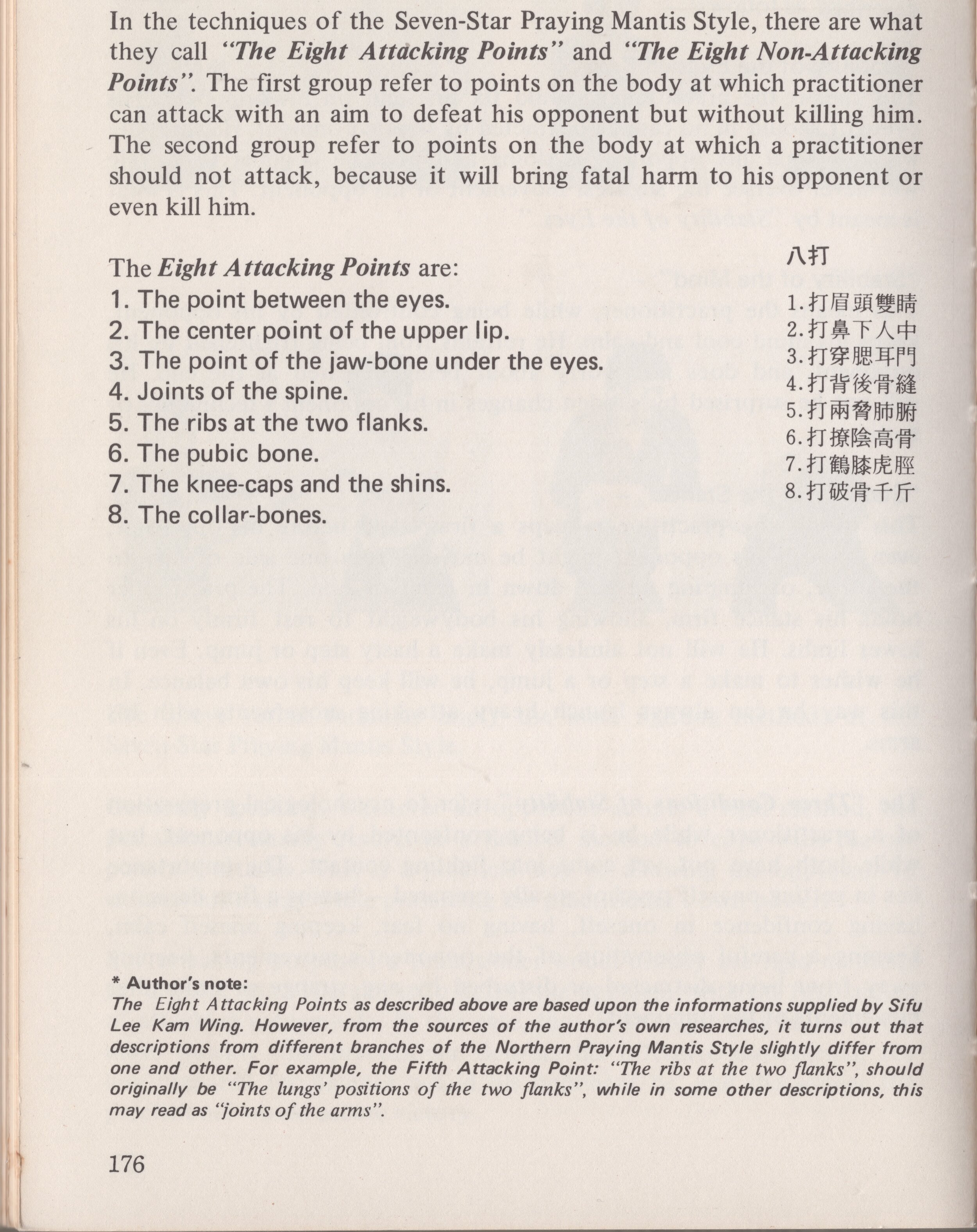

Despite the mass-publication of Bruce Lee’s 8 Hits/8 No Hits list, the majority of the book was focused on Jeet Kune Do, an art of Bruce Lee’s own creation. For a book in English devoted entirely to Praying Mantis and addressing the 8 Hits/8 No hits in the context of the art in which they were often associated with, readers would have to wait five years until 1980.

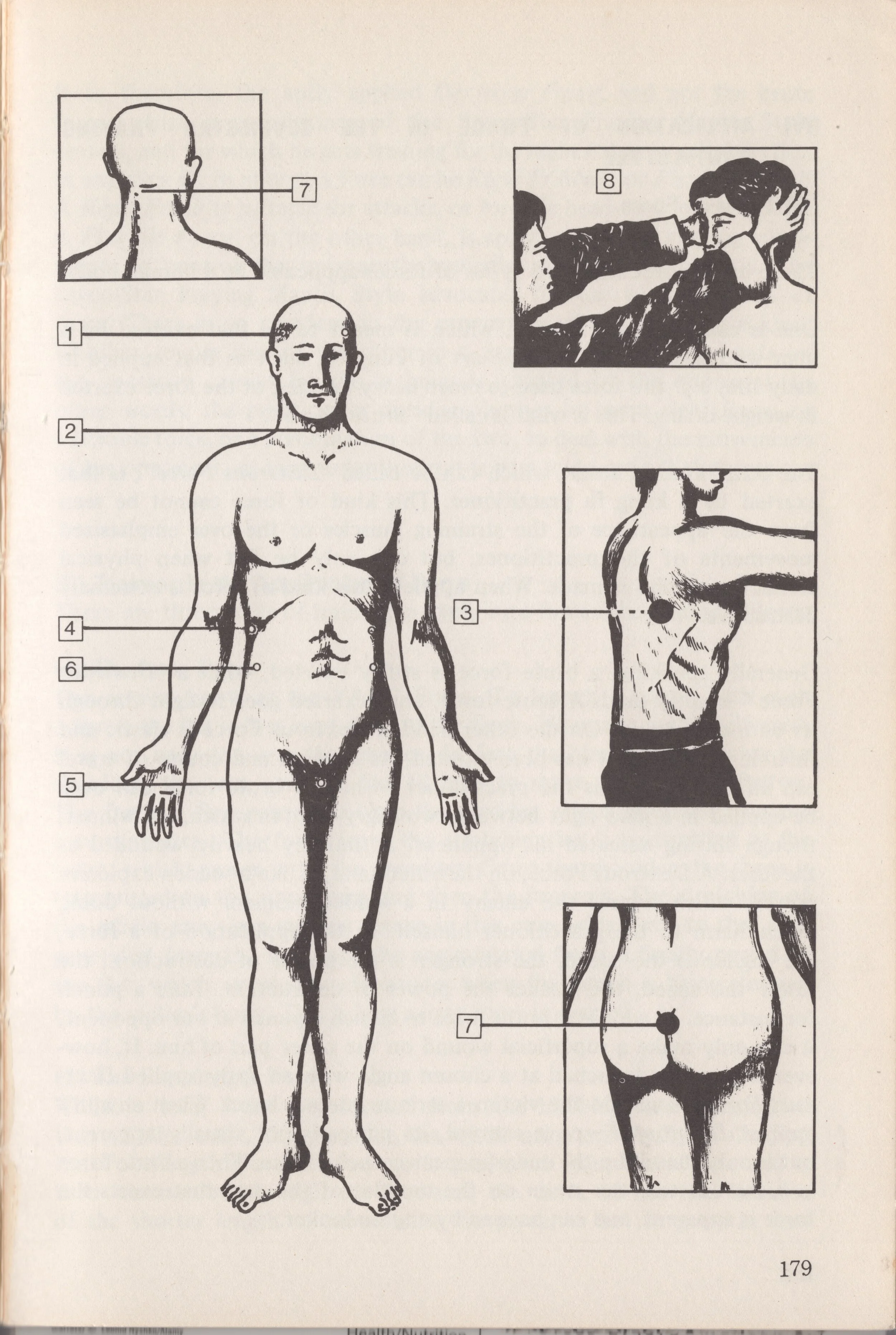

Above: Distributed across the United States by Brendan Lai’s Supply Co., Master Lee Kam Wing’s Seven-Star Praying Mantis Kung Fu was the first time for many English readers to come across the theories of this martial art (8 Hits/8 Non Hits, 8 Hard, 12 Soft, etc.). Below: The 8 Hits/8 Non Hits as listed in the book.

2000’s

A Word From Modern Mantis Practitioners:

Tony Puyot

“In the early 1980’s I was introduced to Master Lee Kam Wing’s book Seven Star Praying Mantis Kung Fu. At the time it was one of the few books written in English about the Praying Mantis system. More importantly, it was the only book that discussed more than a brief account of the history of mantis and a particular form or sequence. One of the things I liked most about the book was that it covered the theories of the mantis system. At the time I focused on theory and understanding, the how and why things worked. I obsessed on every detail of the book and worked diligently to understand every aspect of mantis theory.

One of the Mantis theories in the book is called the eight attacking and the eight non-attacking points. The theories being that to win a fight you attack the attacking points and to kill you attack the non-attacking points. During that time I had an understanding of attacking points I called 有效打 (You Xiao Da) Effective Strike. Targeting specific points on the body played an extremely important part of the effectiveness of the strike. The attacking and non-attacking looked at attacking points as more than effectiveness but a moral choice over target selection.

I studied all the points for years but had difficulty understanding the logic based on my understanding of anatomy and physiology. I speculated that my understanding was limited and I just needed to find someone that could explain it to me. I first asked my friend Master Vincent Black, Hsing-I master, acupuncturist and doctor of oriental medicine. He studied the document and told me some points were valid yet others made no sense. I then asked another friend, Dr. John Chang, a western trained medical doctor and Mantis teacher. He also came to the same conclusion. I continued to ask doctors and martial artist from both western and eastern traditions, all with much the same conclusion.

I decided this document would never make sense, and it was useless for martial artists other than as a historical document. I could only speculate that as this document was very old, the understanding of the human body was limited and prone to speculation. Additionally, medicine of that time period might have had difficulty understanding and treating injuries to some of these targets, therefore labeling “fatal” what is non-fatal in modern times. I developed my own document for attacking points, mine focused on points and left the morality choice of where to attack on the practitioner.

Left: Tony Puyot visits the martial arts shop of the late Praying Mantis teacher Brendan Lai, disciple of Wong Honfan. Right: Puyot looks on as students practice applications at a seminar [Photo courtesy of Boxer’s Rebellion Martial Arts].

Original attacking and non-attacking points from Lee Kam Wing’s Book

Non-attacking

1. Temples

2. Throat

3. Armpit area

4. Side of diaphragm

5. Scrotum

6. Kidneys

7. Top and bottom of spine

8. Ears

Attacking

1. Between the eyes

2. Center of upper lip

3. Cheek under eye

4. Center of spine

5. Ribs

6. Pubic bone

7. Knee and chin

8. Collar bone

Puyot’s 16 attacking points

Body Targets

1. Ribs

2. Solar plexus

3. Stomach

4. Kidneys

5. Liver

6. Groin

7. Knee

8. Shins

Head Targets

1. Eyes

2. Temples

3. Ears

4. Nose

5. Jaw

6. Throat

7. Side of neck

8. Back of neck

Left: Woodcut illustration from a 1500’s Chinese medical text depicting the kidneys: a target that was both listed in the traditional 8 No Hits and incorporated into Puyot’s modern list of targets. Right: Woodcut illustration from a 1500’s Chinese acumoxa point chart, which lists the Ren Zhong (人中): one of the 8 Striking Points that did not make Puyot’s modern list. [8]

Tony Puyot has been practicing Seven Star Mantis since 1982 and Eight Step Praying Mantis since 1985; his martial arts training initially began in 1976, and he also holds several instructor-level ranks in other styles. Puyot made use of his training during his decades long career in security, bodyguard and law enforcement since age 18, while also serving as an arrest and control instructor, firearms instructor and SWAT team trainer. He mostly considers himself a friendly guy that “does some mantis.”

Kevin Brazier

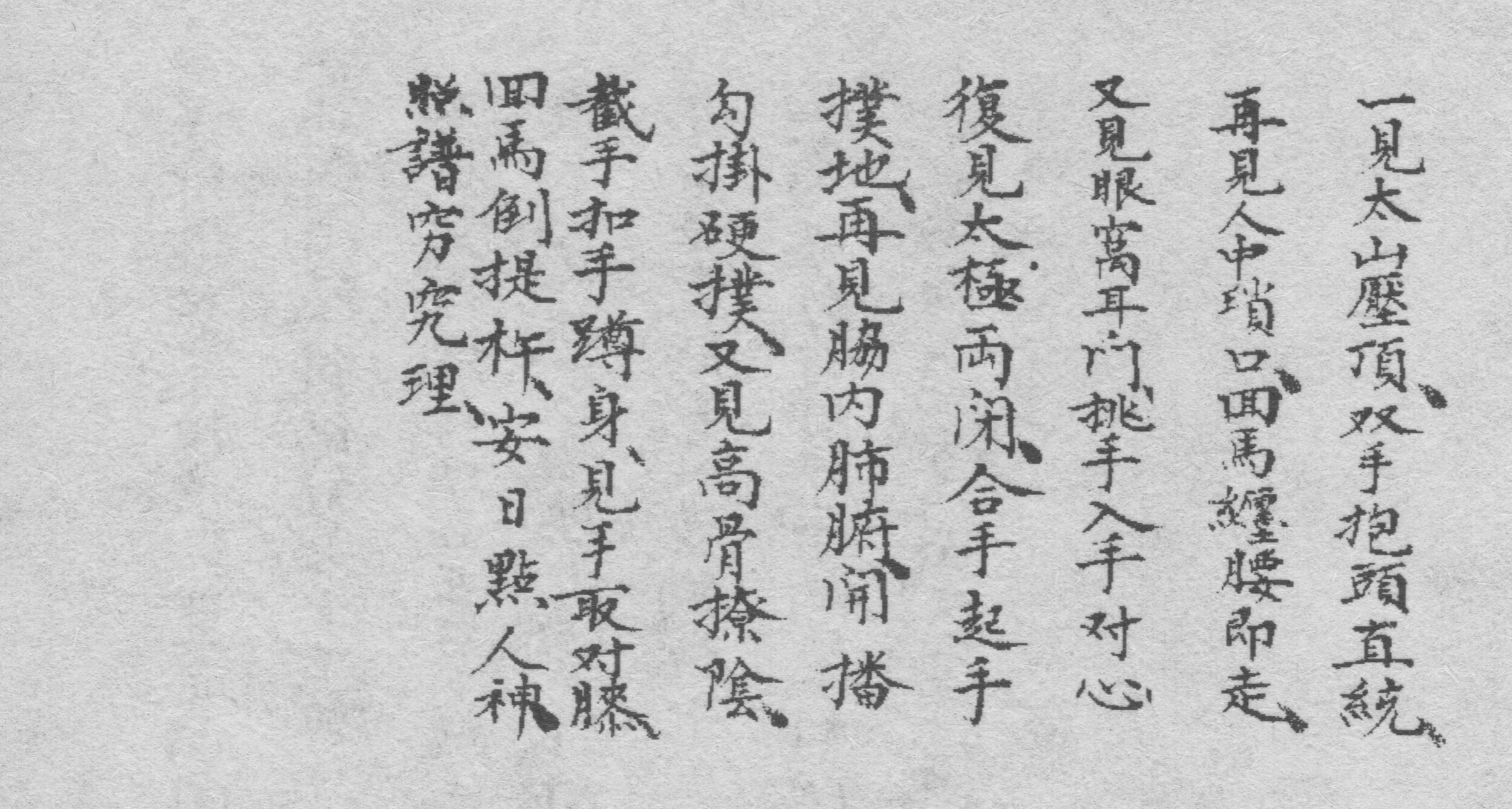

The following excerpt from the Shaolin Authentics translated by Kevin Brazier further demonstrates that the 8 Hits/8 No Hits were not merely an isolated, theoretical list toward the beginning of the manual, but were also seemingly implemented into the training exercises and techniques of early Praying Mantis. Brazier posits that originally, the fighting art of Mantis was trained via various two-person drills that ran through sequences of techniques. Below one sees the 8 Hits/8 No Hits (termed “strikes” and “forbidden” in this translation) referenced nine times in a single page, with additional references to other theories in Mantis sprinkled throughout the described drills (12 Soft, 8 Hard, 7 Long, etc.).

You see your opponent do Mt Tai Presses the Top [1st hard]. Do Two Hands Embrace Your Head and Straight Punches [4th Long].

You then see strikes to Renzhong [2nd strike] and Mouth Sealing [2nd forbidden strike]. You do Returning Horse Wraps the Waist and escape.

Again you see strikes to the eye cavity [1st strike] and Ear Gate [3rd strike]. Do Lifting and Entering [10th soft] hand to the heart.

Again you see strikes to Taiji [4th forbidden] and Bi*[3rd forbidden]. Do Close Hands [defined in 24 short strikes] Raise Hands and Beat the Earth.

Again you see strikes to Feifu inside the rib [5th strike]. Do open up hook hang and hard beating.

Again you see strikes to pubis groin area [6th strike]. Do Intercepting hand Fastening Hand [defined in Fastening Hands] and squat.

You see taking the knees [7th strike]. Do Returning Horse Inverse Lifting of the Pestle [3rd road Luohan Gong].

[Last sentence on vitality omitted.]

*Translator’s Note: Different manuscripts differ significantly on this character.

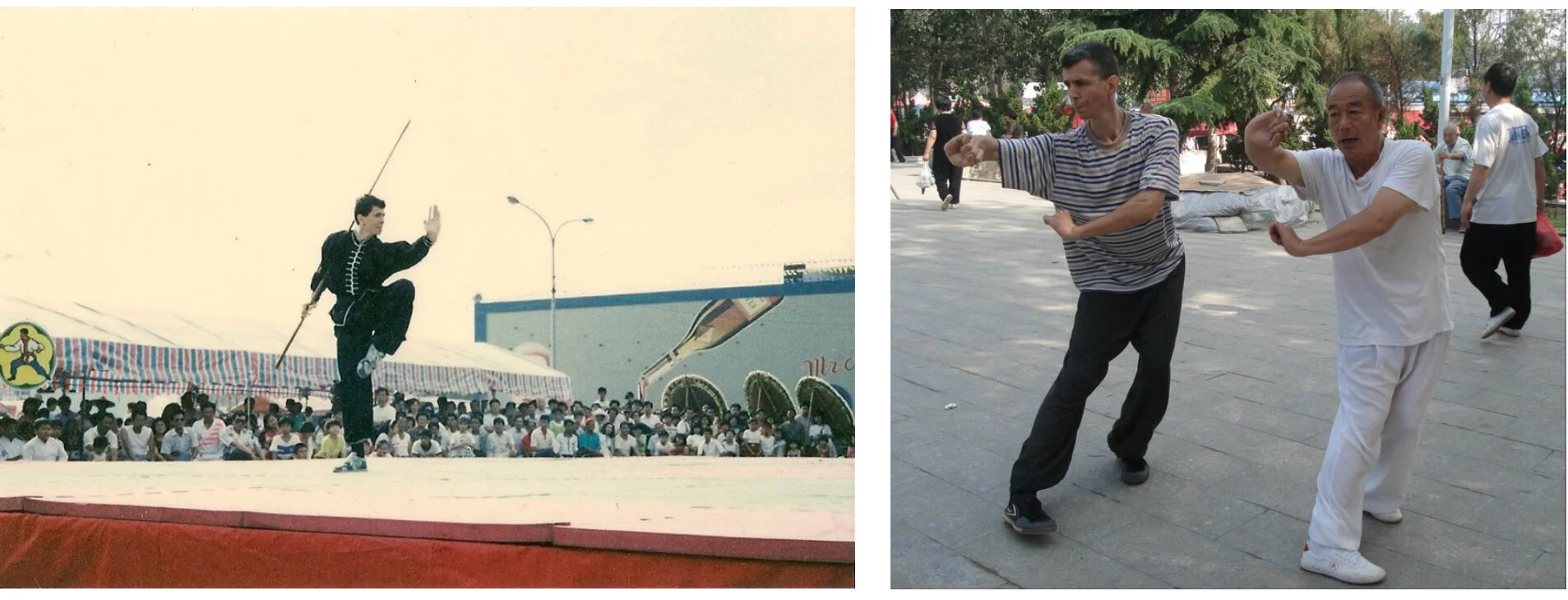

Left: Kevin Brazier performs Mantis while competing at a tournament in Taiwan, circa 1992. Right: Kevin throws an uprooting kick while training under Praying Mantis master Zhou Zhendong.

Kevin Brazier started in Wah Lum Praying Mantis under Art D'Agostino from 1987-1989, eventually heading to Taiwan to train under Shi Zhengzhong. Influential to his approach on Mantis boxing was his 2008 training in China under Zhou Zhendong for four, two-week intensive sessions. During the last 25 years he has acquired multiple versions of old Mantis manuscripts and has been translating and chasing the roots of Mantis.

Alexander Petty

The 8 Targets are not always Accessible

The 8 Targets and 8 Forbidden Targets are always illustrated so cleanly on a drawn figure without clothing, but has it occurred to you that some points simply may not be an option due to an opponents wardrobe? A motorcyclist wears a helmet and a protective jacket; even an average person in a great many parts of the world will wear thick layers while walking about in the winter. Remember that from the quilted gambeson of medieval France to the Ming Jia [明甲] of old China: much of the world’s armor was layers of cotton and cloth. Like modern layers of kevlar fiber found in bulletproof vests, these layers could stop arrows and lessen the effects of strikes. Even cutting through quilted layers with a sword is harder than most realize. Thus wardrobe can potentially limit your access to whichever of the 8 Targets you are seeking, giving you a significant disadvantage in a fight. If you do not believe me try sparring someone as good as you, only give them a motorcycle helmet and layers of clothing topped off with a thick padded jacket. In a friendly sport competition we usually count on the opponent not even wearing a shirt, but as we have already seen, we cannot assume this will always be the case.

Left: A physical altercation between a motorcyclist and a police officer; both wear modern armor protecting targets espoused in the 8 Hits/8 No Hits. Right: Winter layers of clothing are potentially dense enough to mitigate strikes. [Photo Credits: IATSE Stagehand L215 and fzna2.com]

In times past, martial arts had systematic ways of dealing with armored opponents (hence Mantis Boxing’s inclusion of locks, throws and weapons, not merely strikes); this specific scenario is not practiced much nowadays. Did you know that Judo has an entire two-person drill meant to be done in full samurai armor, thus giving the practitioners a chance to utilize techniques specifically for armored opponents? (古式の形 Koshiki no kata, literally “Ancient style form”). Very few Judo schools currently practice this kata. From the plethora of Historical European Martial Arts manuals we see much the same thing: schools in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance developed specific ways to counter armored enemies. Should we then don armor for every single training session? Of course not, as the scenario of fighting in or against armor is on the periphery of the average citizen. I am simply saying that a scenario may occur even in modern times, as it has in ages past, where vital targets (the 8 Hits/8 No Hits) are shielded from your strikes; never practicing that scenario or searching your own martial art for the answers in such an encounter seems neglectful.

Above: Woodblock print, possibly late Edo period: two samurai wrestle in armor over a knife. Wardrobe certainly influenced martial techniques. As an example: Filipino knife fighting includes cuts to the opponent’s extended arm, which works well in a tropical climate where most inhabitants would be wearing short sleeves or no shirt at all. Such cuts to the opponent’s wrist are notably absent in the more close range style of classical Japanese knife fighting (tantojutsu), where in the winters of Japan: even an unarmored opponent’s limb could be wrapped in a dozen layers of clothing.

Methods to Strike the 8 Targets are not always Obvious

Whether due to popular culture or our own lack of imagination, the topic of striking vital points too often conjures a specific image of a master forming their hand into some exotic shape before striking “the killing blow”; in reality, targets from the 8 Hit/8 No Hits are not always struck with the hand. Take for example number seven of Wong Honfan’s 8 Forbidden Targets: the tailbone. How does one even attack this point? Perhaps ask the opponent to freeze, run around behind them, crouch, and punch them in the tailbone? One answer for how to hit this area lies not in striking, but throwing.

Above: Six Harmonies Praying Mantis master Hu Xilin steps in to trap the leg of his opponent while chopping down from above and managing the opponent’s arms, all resulting in a throw that will force the opponent to fall without the aid of any of their limbs. Variations of such throws in Mantis sometimes aim to make the opponent land solely on their tailbone.

Mantis has a variety of dramatic throws: throws that percussively strike the opponent as they are performed, throws that wheel the enemy around and force them to land on their head, etc. Yet there exist a few throws that simply trip the opponent and forcefully sit them down. When practiced on a mat or a springy gym floor, these type of throws look useless as, aside from perhaps a positional advantage gained, no obvious damage seems implied with the opponent left in a simple sitting position on the ground. Yet outside on the hard ground or concrete, with enough force and positioning, the Praying Mantis practitioner is actually forcing the opponent to catch all of their weight on their tailbone; potentially a fight-ending throw, if pulled off successfully, and a unique way to enact the 8 Hits/8 No Hits.

Striking a Specific Point on a Resisting Opponent is Difficult

Knowing a target is not enough: you also have to issue enough force to effect said target, avoid enemy attacks, employ techniques and strategies to create openings, etc. So we see that knowledge of vulnerable points is only 5% if even of martial arts training. Everyone by nature knows the eyes are vulnerable: that does not mean they have the speed, skill, strength, strategy, and spirit to effectively strike there in a fight.

Our teachers past acknowledged this reality, and so we see a variety of strategies and techniques espoused in the manuals of Mantis Boxing, all with varying degrees of appropriateness or difficulty depending on the situation. Wong Honfan for example held that joint locks were easier to employ than striking acupoints:

Locking joints and striking acupoints are major skills in boxing arts, and everyone with even a modicum of study is aware of their advantages and disadvantages. Striking acupoints is a challenge to even comprehend and is not easy to apply without a deep level of study and training, but once you have fully realized the methods of twisting bones and sinews, then everywhere the limbs can bend and move becomes a target. [4]

- Wong Honfan, 1955

Above: Bone breaking/displacing technique of Praying Mantis, demonstrated by Wong Honfan’s teacher Luo Guangyu (right) and by his students, Mai Huayong & Dai Jincheng (left). Mantis Boxing seeks to check the opponent’s limbs while striking, and due to this constant limb-to-limb contact the practitioner is in a unique position to flow into a joint lock. Wong Honfan held that there were more opportunities to place your opponent in a lock than to strike a specific acupoint.

Acknowledging the difficulties of striking with precision is by no means meant to discourage the reader from pursuing a high level of skill. Students should certainly learn and practice where to strike and how, thus the origin of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits. In a life-or-death struggle however, they should also realize the full range of options including more easily employed techniques, whether it be a joint lock or simply running away!

Why Eight?

Is it not interesting that our teachers past decided to study the body, compile a list of lethal targets and non-lethal targets, and the two corresponding lists happened to match numerically? Eight and Eight. This most likely has something to do with a worldview dating back literally millennia.

Right: Fuxi (伏羲), the legendary figure of Chinese myth who devised the Eight Trigrams in order to achieve mastery over the world. Left: A Ming-Era longevity text depicting the Eight Trigrams relationship to the Five Elements. [9]

Without detouring heavily into Chinese philosophy, religion and myth, the number eight was (and to a certain degree, still is) considered an auspicious number in Chinese society. Eights coupled together (“88”) were also seen as indicative of fortuitousness and success. The reader can research the history behind this phenomena at their own leisure; for the purposes of this article it is simply enough to say that the formation of the 8 Hits/8 No Hits were likely influenced by this worldview.

Left: A diagnostics chart with a table of correspondences between the Eight Trigrams and the internal organs, “because a human being resembles the heavens.” 1599 AD. Right: Illustration of the Eight Trigrams Massage; further evidence the number eight permeated all sorts of disciplines in China, from medicine and massage to martial arts. [10]

Alexander Petty began studying the Wong Honfan tradition of Praying Mantis as a teenager under Stephen Cottrell. His ongoing efforts to preserve and share the art led to the creation of the Archives at the Ravenswood Academy, where over forty Wong Honfan manuals have been uploaded. Once rare and inaccessible, these books are now available to all for studying and translation efforts.

Will Wain-Williams

The concepts of “8 Hits 8 Non-Hits”, “7 Long 8 Short”, “8 Hard 12 Soft” and others are often considered as central to the construction of the Mantis system and are mentioned at the beginning of every manuscript old and new. However, these concepts are far from unique to Mantis. China never had a concept of copyright or authorship, and it was common to plagiarise the works of others. These concepts can in fact be found across the majority of northern styles in one form or another, with considerable variation at that. Northern Chinese martial arts are, for the most part, derived from weapons methods, such as the spear and the sabre. If you look back at weapons manuals from the Chinese military in the Ming Dynasty, you can find the earliest references to a lot of these theories, and it is from there they have been adapted into the modern empty hand systems we practice today.

Will Wain-Williams (left) practices the Taiji Mantis system of Cui Shou Shan under his teacher Zhou Zhen Dong in Yantai, China. Will lived in China for over a decade training and researching Chinese Martial Arts, which he documented on his website and Youtube channel Monkey Steals Peach (right).

Historical Roots

Above: Evidencing Will Wain-Williams point is a Taiji manual from 1936 which, curiously, lists “eight permissible targets, eight emergency targets, and eight forbidden targets.” The locations have significant overlap with the list from Praying Mantis, but are not entirely the same. To view the list as well as an entire English translation by Paul Brennan, click Here.

The list of 8 Hits/8 No Hits are essentially a study of anatomy from a martial perspective. How far does such an idea stretch back, and when was it codified into a list as part of Mantis Boxing? Noting areas of where to strike in terms of efficacy is older than civilization itself. There are bone arrow heads dating back 9000 years ago in China; skilled hunters undoubtedly noticed the effects of shooting prey in the organs versus the leg. One can only imagine that the same observations were made in terms of human conflict while warring with other tribes.

Above: 1000 Years Before Paper: A 3000 year-old Chinese axe from the tomb of a female general, Fu Hao. Fu Hao’s tomb held over 100 weapons, including bronze knives, axes, and arrows. Undoubtedly she and the 13,000 soldiers under her command had some degree of knowledge concerning where to strike an opponent in combat, no matter how informal. [11]

Archeological implications aside, the millennia-long written records of China are scattered with references of warriors hitting specific locations on their enemies for specific results. Accounts include everything from the brief and tangentially-related:

“Enraged, Ch'ang-wan struck Duke Min with his fist, breaking his neck.” - Spring and Autumn Annals, the Twelfth Year of Duke Zhuang’s Reign (682 BC) [12]

To the more specific:

Whenever he fought people, he always made use of acupoints, targeting points that would cause death, fainting, or muteness, as indicated on those bronze statues with the acupuncture maps. (Biography of Wang Zhengnan, 1669 AD) [4]

It may never be known how the 8 Hits/8 No Hits were added to Praying Mantis, and by whom, but these historical references certainly illustrate that striking acupoints or specific regions had long been a body of knowledge, whether existing un-written through a warrior’s personal experience or taught orally as a theoretical body of knowledge within a martial arts school.

Left: A young Mantis Boxer strikes a dramatic pose: Wong Honchiu (黃漢超 1936-2018). Wong Honchui not only studied under Wong Honfan, but would eventually graduate from Harvard and go on to receive his Doctorate. His Ph. D. dissertation: “GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURES IN NORTHERN SUNG CHINA (960-1127).” Right: How far back do the concepts of Mantis go? A central theme in one of his published works, Wong Honchiu held that “It is quite obvious that Wang Lang, the creator of Praying Mantis boxing, had drawn some inspiration from Ch’i chi-kuang [Qi Jiguang 1528-1588].” [13]

Epilogue

Deep within the martial arts world, the niche subject of attacking specific or secret points on an opponent in order to cause paralysis or even death simultaneously evokes images of both the fake and the authentic. On the fake side, charlatans abound with unproven claims and ineffectual theories. In contrast, the authentic is represented by undeniable facts: modern sport fighters have taken body shots and immediately crumpled; boxers have had their internal organs (such as the spleen) ruptured by their opponent’s strikes. Indeed, lethal disruption of the heart’s rhythm as a result of a blow to the area directly over the heart is so well documented in modern sports accidents and medical science, it has been given a name: Commotio cordis. One wonders what stories may have evolved in Ancient China when bystanders witnessed similar events. What investigations and practices were prompted by martial artists looking to survive?

It would seem this subject remains to some degree shrouded in misinformation and mystery as, to this day, writings on the topic remain unavailable or even undiscovered. Enter A Study of Attacking Vessels, Acupoints, and Vital Areas [點脈•截穴•要害•之研究] by Pan Maorong [潘茂容]. This is a rare book. The World Catalogue lists only one of these books in the world, in (of all places) Ohio University. We know because one of our associates kindly went there and scanned a copy so the text could be preserved, uploaded to our Archive and shared with all. View it by clicking HERE.

Left: A diagram on striking vital organs. Center: The cover of Maorong’s book. Right: An application of a Praying Mantis technique from the foundational form Beng Bu.

Pan Maorong’s book is filled with intriguing diagrams of human anatomy and demonstrations of martial applications. Pan in the introduction defines 點脈 (dian mai, more commonly known as dim mak) as striking blood vessels to cause blockages and induce illness, 截穴 (jie xue) as striking nerves to cause numbness and induce effects such as paralysis or dementia, and 要害 (yaohai) as striking vital areas to disrupt organ function. As a fighter who studied under the Mantis master Luo Guangyu, could Pan Maorong have something insightful to say about Mantis’ 8 Hits/8 No Hits?

Sadly, translators have informed us they cannot take up the task of properly converting this book to the English language as it is incomplete. What we have is only one volume of a three volume series. Hopefully the remainder of these lost manuals surface so their contents can be shared. If you have any information relevant to the location of these manuals, please e-mail theravenswoodacademy@gmail.com

Above: Diagrams of human anatomy and martial applications. Could Pan Maorong have had something to say directly about the 8 Hits/8 No Hits in one of his lost manuals?

Special Thanks

This article has relied heavily on the translation work carried out by Paul Brennan of Brennan Translations (any mistakes contained in the article above are our own). Of the forty Wong Honfan Praying Mantis books provided by the Ravenswood Academy, Brennan has currently translated a staggering nineteen in only the last few years. View over one hundred translated Chinese martial arts manuals here at his site: https://brennantranslation.wordpress.com/

Notes

[1] Diagram from Lei Ching (類經) by Chang Chiehpin (張介賓), published in 1624. Chang's first book on medicine gained wide use among physicians of China. It purports to explain and interpret the Nei Ching (內經), a medical work traditionally attributed to the legendary emperor, Huangdi 黃帝. In reality, it is largely a crystallization of Chang's opinions based on long experience as a practitioner and many years of painstaking study. Huang Tsunghsi writing in 1671 asserts that it was the most popular and valuable work on medicine in his day. See http://www.dartmouth.edu/~qing/WEB/CHANG_CHIEH-PIN.html (Our thanks to Kevin Brazier for supplying the image from the Lei Ching and pointing out this connection which, previously, we had only suspected but had no proof).

[2] Thanks to Brendan Tunks of mantisboxing.com for providing these dates.

[3] Thanks to Brendan Tunks for letting us know that this photo was first published in the 2013 book Laiyang Tanglang Quan. Thanks to Angelo D’aria for tracking down this rare photograph in 2017 and sharing an even higher resolution version .

[4] Translated by Paul Brennan and sourced from Brennan Translations. View these and other works at https://brennantranslation.wordpress.com/

[5] Photo courtesy of https://www.hfwong-mantis.com/

[6] Photo courtesy of https://www.hfwong-mantis.com/

[7] Photo courtesy of Bruce Lee Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/BruceLee/posts/during-his-recovery-from-a-near-career-ending-back-injury-to-his-sacral-nerve-in/10160159419495634/

[8] Credit: Kidney (shen) and Portal of Life (mingmen), Chinese, Ming. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Acupuncture chart: Acu-moxa points for heatstroke with coma. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

[9] Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) terms and conditions https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 Credit: GGraphic from Ming Chinese longevity text, woodcut. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Credit: Chinese woodcut, Famous medical figures: Emperor Fuxi. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

[10] Credit: Diagnostic chart: body as microcosm, Chinese woodcut. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Credit: C20 Chinese medical illustration in trad. style: Hand massage. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) terms and conditions https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

[11] Photo courtesy of CTGN. https://news.cgtn.com/news/304d444f346b7a6333566d54/index.html

[12] See R. K. Norris’ Tung Chung-shu. https://archive.org/details/ChunqiuFanlu/mode/2up. Other translations simply have Cha’ng-wan “seizing”, not “striking.” See for example Harry Miller’s The Gongyang Commentary on The Spring and Autumn Annals: A Full Translation https://books.google.com/books?id=996_BwAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PR2-IA2&lpg=RA1-PR2-IA2&dq=duke+min+neck+year+spring+and+autumn+annals&source=bl&ots=KjEo0uT9VA&sig=ACfU3U3-f2ElqfH42QezX_5yxGjY37wnUA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwic4pzUzf_oAhWBQs0KHbzsC5AQ6AEwAHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=false

[13] Photograph of Wong Honchiu courtesy of hfwong-mantis.com. Quote from 戚繼光拳經螳螂拳證義.

This Article was first published July, 2020.

![Seated Above: Praying Mantis master Fan Xudong (范旭东), unverified birth-date between 1840 and 1875, unverified death-date circa 1936. [2][3] Below: Fan Xudong’s personal copy of the Shaolin Authentics, listing within the 8 Hits/8 No Hits.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c1bd8403596ec73f1a54c6/1591497358670-XU4PPLNZQJQAUM7QDNKX/Xiao-ShuBin-Fan-XuDong-e-Hu-YongFu+2+copy+2.jpg)

![Above: Bruce Lee had over a dozen of Wong Honfan’s Praying Mantis books which he studied, translated and gave to senior students. A forthcoming article will outline in detail Bruce Lee’s connection to Praying Mantis Kung Fu. [7]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c1bd8403596ec73f1a54c6/1587684679015-5096FZISPHF16ZPG7THD/1*ifZbaCAecI410OL_ypSRGQ.jpeg)

![Left: Tony Puyot visits the martial arts shop of the late Praying Mantis teacher Brendan Lai, disciple of Wong Honfan. Right: Puyot looks on as students practice applications at a seminar [Photo courtesy of Boxer’s Rebellion Martial Arts].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c1bd8403596ec73f1a54c6/1587764769131-EWDOGU349NCKLLOZAXWR/New+Project%286%29+copy+8.jpg)

![Right: Fuxi (伏羲), the legendary figure of Chinese myth who devised the Eight Trigrams in order to achieve mastery over the world. Left: A Ming-Era longevity text depicting the Eight Trigrams relationship to the Five Elements. [9]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c1bd8403596ec73f1a54c6/1591735151254-M4W5G8XQSA50O4EYERAL/New+Project%2834%29+copy+2.jpg)