Of Rope Darts, Chain Whips and Meteor Hammers: A Visual History of Flexible Weapons in China

1400’s

Circa 1465-1487: Du Qian admires Xue Yong’s Meteor Hammer Skill

Above: Image from the Shui hu ren wu quan tu (水浒人物全图) by Du Jin (杜堇). Du Jin was a Chinese painter whose specific date of birth and death are unknown, but he was active between 1465-1487, giving a reasonable date-range for the production of the above piece. As for the characters depicted, they are from the Water Margin story, a tale of fantastical bandit-adventures loosely inspired by historical events. Wue Yong wields the meteor hammer and himself had been in the military, but having been kicked out he lived as a wandering medicine hawker who did martial arts performances in the marketplace before becoming a bandit. The onlooker Du Qian also had a more recent military background in the story, and seems to have the end of a meteor hammer looped around his left wrist. [1]

Circa 1465-1487: Fan Rui beholds a Magic Sword with a Meteor Hammer draped behind his back

Above: Another piece produced by Du Jin. Here the daoist priest Gongsun Sheng exhibits a magical sword while Fan Rui watches, holding meteor a hammer. Curiously, the weapon Fan Rui used was referenced in the period sources not merely as a meteor hammer, but as the An Hei Liuxing Chui (暗黑流星錘). “An” being hidden or concealed and Hei being "black" but in a martial arts context possibly having the meaning of being especially wicked, cruel or injurious.

1600’s

Circa 1600: Mounted Warrior with Flexible Weapon in History of Three Kingdoms

Above: A scene from San Guo Zhi (History of Three Kingdoms 遺香堂繪像三國志) in the Yi Xiang Tang edition. This print is significant as it is one of the few to depict a flexible weapon being wielded from horseback. The small radial lines stemming from the meteor hammer indicate that this weapon may have had spikes or claws, and been intended to snag the clothing of the pursued and pull them from horseback. See more detailed illustrations of such weapons further below.[2]

Date Uncertain, perhaps late Ming Dynasty (1600’s): Double Chain Whips

Above: Wu Yong uses dual copper chain whips to break up a fight. Below: A character from the novel Water Margin, Wu Yong was a strategist and teacher known for his brilliance.[3]

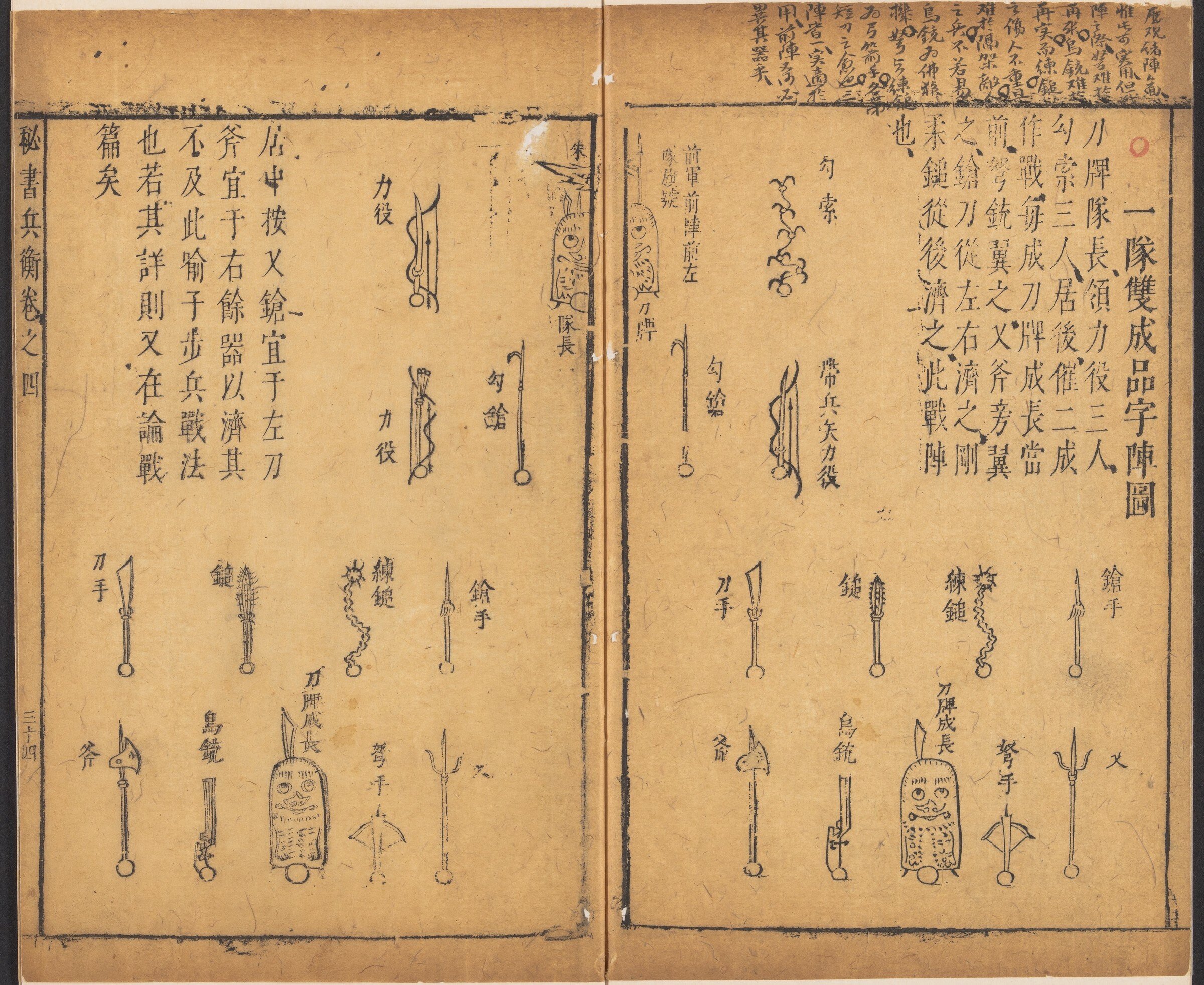

1609: Late Ming Encyclopedia depicts Three Rope Weapons

Above: In 1609 a father-son team published a massive encyclopedia entitled San Cai Tu Hui (Collected Illustrations of the Three Realms 三才圖會). Amongst other weapons, here they list flexible weapons (from left to right): Long Zha (龍吒, lit. 'Dragon howl' in context it means 'Dragon claw'). Xing Chui (星鎚, lit. 'Star hammer'). Mei Zha (梅吒, lit. 'Plum howl', in context it means 'Plum flower claw'). [4]

Above Right: It is interesting to note that for the Japanese version of the San Cai Tu Hui, the illustration for the Dragon Claw flexible weapon was swapped out for what would now be commonly called a grappling hook.

Between 1620-1652: Playing Cards depict Meteor Hammer

Above: Shui hu ye zi (Water margin leaves) was a masterpiece of early Qing created by Chen Hongshou (1598‒1652). It contains 40 illustrations depicting the outlaws in the novel Shui hu zhuan (Water margin). Ye zi (leaves) were actually a set of printed playing cards, to be used in a wine drinking game at a banquet. A player drew a card and would empty a cup of wine according to the meaning of the painting on the card cover and the instruction written on the card. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, such games flourished, and became very popular. According to Tao’an meng yi (Reminiscences in dreams of Tao’an), by Ming writer Zhang Dai, Chen Hongshou completed this work in four months. The paintings show all of the outlaws of Water Margin. The work became very popular after its publication. [5]

1621: Horse Entanglement Weapons and Siege Defense

Weapons from the Wubei Zhi (武備志) one of the most comprehensive military books in Chinese history comprising a multitude of volumes over 10,000 pages.

Above: Popular imagination often has a lone martial artist wielding a flexible weapon in a duel scenario, but some such weapons may have been crafted for entirely different purposes despite their resemblance to meteor hammers and rope darts. The above clawed weapon in the center was intended to be thrown in the hopes of entangling enemy cavalry, while the weapon on the far left was supposedly meant for wall defenders to catch enemy troops, raise them up and then drop them. The weapon on the far right does however depict a double-headed meteor hammer.

Between 1621-1627: Spiked Meteor Hammer

Above: A spiked meteor hammer listed amongst other weapons in a 12 volume work on military affairs (judging terrain, weather, tactics, armor, etc.). Curiously, this manual places the meteor hammer in a military context (at least in theory), and not in the hands of a fictionalized hero or in a civilian setting as part of a village martial art. [6]

Above: Lian Chui 錬鎚 (Chain Hammer) listed amongst other weapons.

Late Ming (Early 1600’s): Meteor Hammer wielder in Siege Engine

Unconfirmed source (perhaps 康濟譜 Kang Ji Pu "Relief Aid Manual," a late Ming military manual)

Above: Image from a Late Ming Dynasty military manual, with a meteor hammer wielder seated in the middle column, second row from the top. It should be noted that the author’s main purpose was portraying the engine: the inhabitants were written in as aesthetic filler and certainly do not represent the standard armor or weapons of Ming military troops.

1800’s

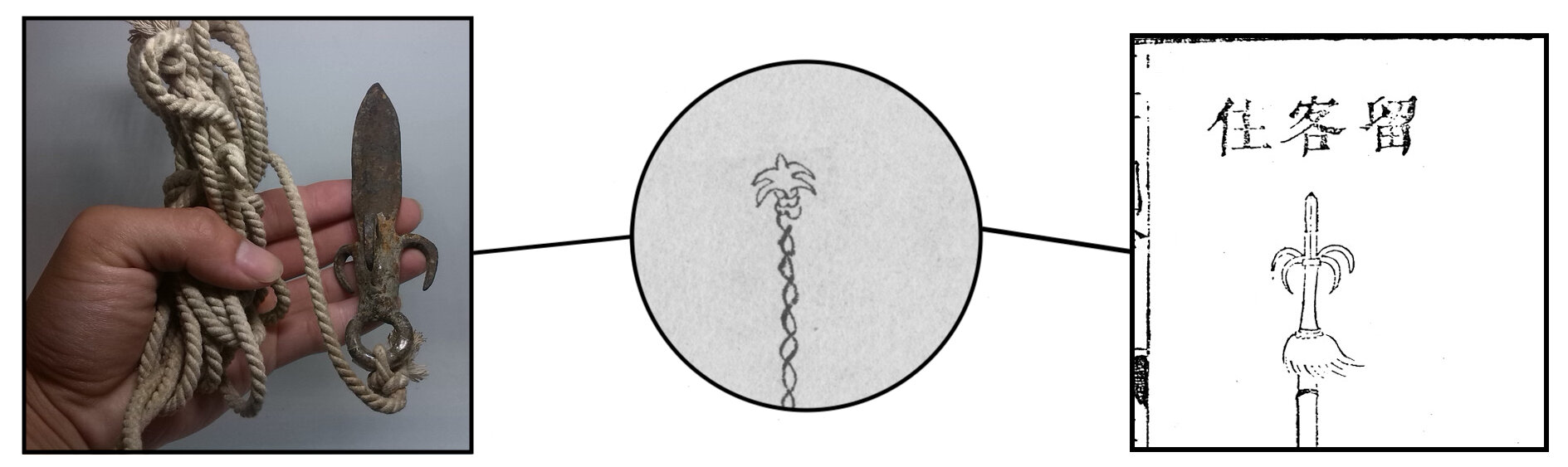

Date Uncertain: Praying Mantis Fist Manual depicts Rope Dart

Above: Image from the Shaolin Yibo Zhenchuan (少林衣钵真传), a praying mantis boxing manual with various theories, weapons and empty hand applications. [7]

Above Center: Detail from the Mantis Boxing Manual that depicts a Rope Dart. Above Left: A modern day person holds an example of what a rope dart with a forward-facing blade and rearward-facing hooks may have looked like. Above Right: The rope dart looks stylistically similar to types of spear depicted in Ming-Era books. While it can be theorized that spear heads may have made excellent rope darts, there is currently no historical evidence of the former being re-fashioned into the latter.

1827-1830: Chinese Hero captured by Various Rope Weapons

Above: Depicting no less than a staggering thirteen meteor hammers and claws, this piece features a hero from the Chinese classic novel Water Margin. Japanese artist Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) produced this colored woodblock titled “Ruan Xiao’er (Ritchitaisai Genshoji), from the series ‘One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Popular Water Margin (Tsuzoku Suikoden goketsu hyakuhachinin no hitori)’”. In the original popular tale, Ruan Xiao’er (阮小二) is an expert swimmer who carries out deeds of espionage, sneaking onto enemy boats for sabotage. This dramatic print depicts the characters capture. [8]

Above: Another print by the same artist, depicting Xie Zhen, a skilled martial artist and hunter of tigers in the Water Margin. Xie Zhen would meet the same fate as Ruan Xiao’er: being captured by multiple hooked rope weapons. With all these similar stories of capture, one cannot help but wonder if the meteor hammer and flying claws were ever specifically thought of and utilized as criminal capture weapons, thrown by the pursuer to snag fleeing quarry. The tsukubō, sodegarami and sasumata for example are all period examples of Japanese weapons designed to capture suspects for trial without killing them; the skill of modern lasso practitioners also adds plausibility to this idea. However the image of a hero caught by many foes may have simply been a dramatic literary device with little basis in historical practice.[9]

1829: A Quarrel between Heroes - the Meteor Hammer in a Duel

Above: On the left, Liu Tang, a smuggler who operates out of Shandong, faces off against Lei Heng, the Winged Tiger, who wields a meteor hammer. More imagery from the Water Margin novel. Though the print is unsigned, this is once again a Japanese artist depicting Chines heroes. [10]

Circa 1845: One of the 108 Heroes of the Water Margin with Meteor Hammer

Above: Detail from a group setting with a man armed not only with a meteor hammer, but also with a sword and spear. [11]

Date Uncertain, most likely Qing Dynasty (1800’s ?): Water Margin characters with Meteor Hammers

Above: A variety of meteor hammers are depicted in this scroll, some with smooth heads while others are more faceted; some with chain, others with cord. Below Right: A meteor hammer with a flag attached near the end. [12]

1800’s: Chinese Street Performers with Meteor Hammers and Chain Whips

Above: Depicted next to a sword-swallower, it is clear that the context of this and other depictions of the meteor hammer and chain whips is in that of performance art on the streets, and not martial combat. [13]

Above Right: Unlike the typically portrayed performer with a double-headed meteor hammer, the artist on the right wields two, three section chain whips.

Above: From a 19th century book depicting Beijing street vendors, it seems that the rope dartist was often a jack-of-all-trades; martial artist, performer and medicine maker. Here the rope dartist is seen tending to a wound (note the handle-sized length of bamboo on the rope dart that acts as a slider).

Early 1900’s

Early 1900’s: Master plays with Double Meteor Hammers

Above: Body guard to the emperor and trainer for the imperial guard by 1899, Zhao Xin Zhou 趙鑫州 (1876 - at least 1927) is the martial arts practitioner in this photograph depicting double meteor hammers. In his later years Zhao Xinzhou, having passed on his style and pleased at the notion of leaving the martial world, opened a store called Deji Guwan (Virtuous Classics Antiques), where he spent his remaining years in happiness given his particular liking for curio and deep understanding of art. He had three sons and one daughter. [14]

Date Uncertain, (1890 - 1910?): Street Performer with Chain Whip at his feet.

Above: Earning a living by exhibiting: martial artists attract a crowd in the hopes of earning bread. The bottom right corner of this photograph reveals the links of a chain whip lying on the ground. Credit to Neil Anderson for penning an article that first pointed out this detail. [15]

1919: Street Performer with Rope Dart/Meteor Hammer on Ground

Above: A street performer in Vladivostok with what appears to be a meteor hammer at his feet. Note the hollow bamboo grip allowing the rope to slide. [16]

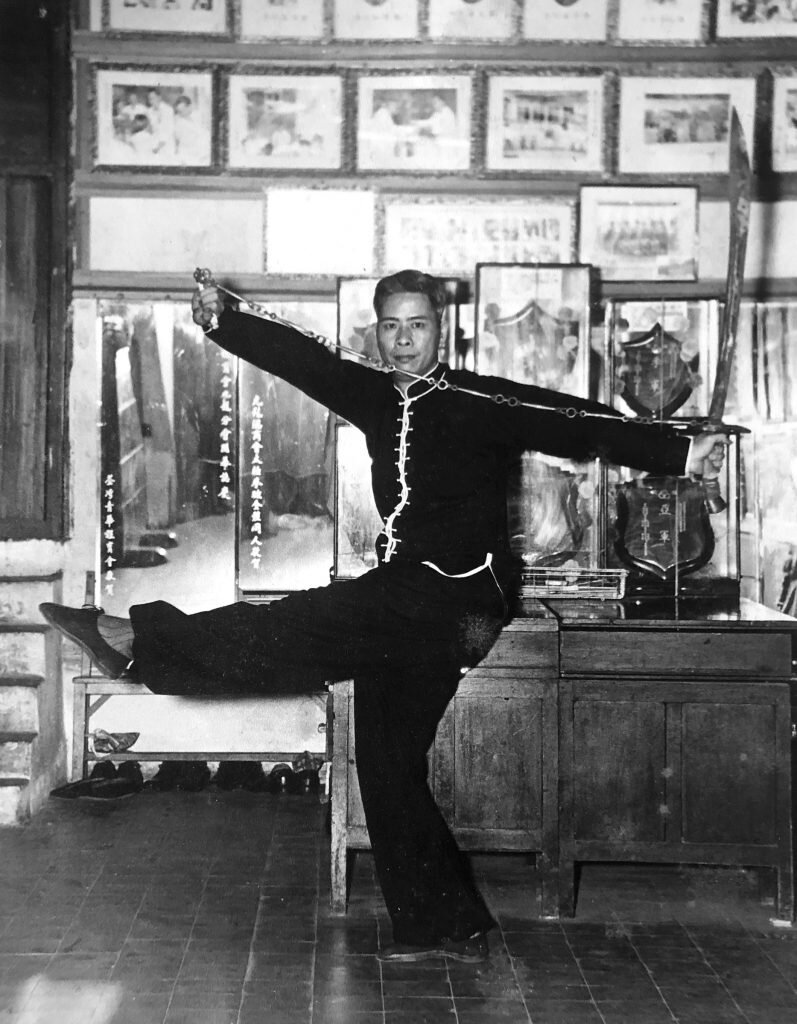

Acknowledgments

This gallery was assembled by the Ravenswood Academy. Please consider supporting us HERE. Thank You.

Above: Praying Mantis Master Wong Honfan (1915 - 1974) poses with chain whip and broad sword. One of Ravenswood’s goals is to preserve the martial school that Wong Honfan passed down. Thanks to Wong Ngai Yin (黃毅英) for providing this photograph. View more at: www.hfwong-mantis.com

Appendix

Combination Flexible and Staff Weapons

Be it known that this article has entirely ignored weapons with staff-like elements: items with their own rich history in China that can be explored elsewhere at the reader’s leisure.

Above Left: Yet another protagonist from the Water Margin. Above Right: Examples of an entirely different flexible weapon from an old military encyclopedia. [17]

Above: More combination flexible and staff weapons from the Shui hu ren wu quan tu.

Fire Meteor Hammers

Above: Fire Meteor Hammer performer depicted amongst a collection of Chinese folk portraits. Date uncertain, most likely Qing Dynasty (1800’s?).

Fire Meteor Hammers (lit. 火流星, i.e. meteor hammers that were ignited with live flames) certainly existed in China’s history, though they seem to have been more artistic than martial in nature:

They were practiced as part of festivities during temple fairs and holiday celebrations. They were also commonly shown as part of the performances of traveling circuses and acrobatic troops. During Chinese holiday celebrations such as the lantern festival the fire spinners would traditionally lead the huge street parades. During these festivals the narrow streets of the traditional Chinese cities would be packed with people. The fire spinners would go first using the spinning fire to open up the street to let the parade of lanterns, lion or dragon dancers, floats, altars, gods, and spirit warriors through the crowds. The meteor hammers used in these demonstrations were almost always double ended. [18]

Traditional Chinese Huo Liuxing Chui differ from the kind used by modern performers in the west as instead of using flammable liquid for fuel they would use a metal cage filled with burning coals. During the performance the coals will emit showers of sparks giving the "meteor" it's burning tail.

Water Meteor Hammer

Above: Date Uncertain, most likely Qing Dynasty (1800’s?)

Water Meteor Hammers existed most likely as either a training tool and/or game. The bowl at the end of the rope was filled with water, centrifugal force being the only thing that kept the water from spilling once the meteor hammer was in constant motion.

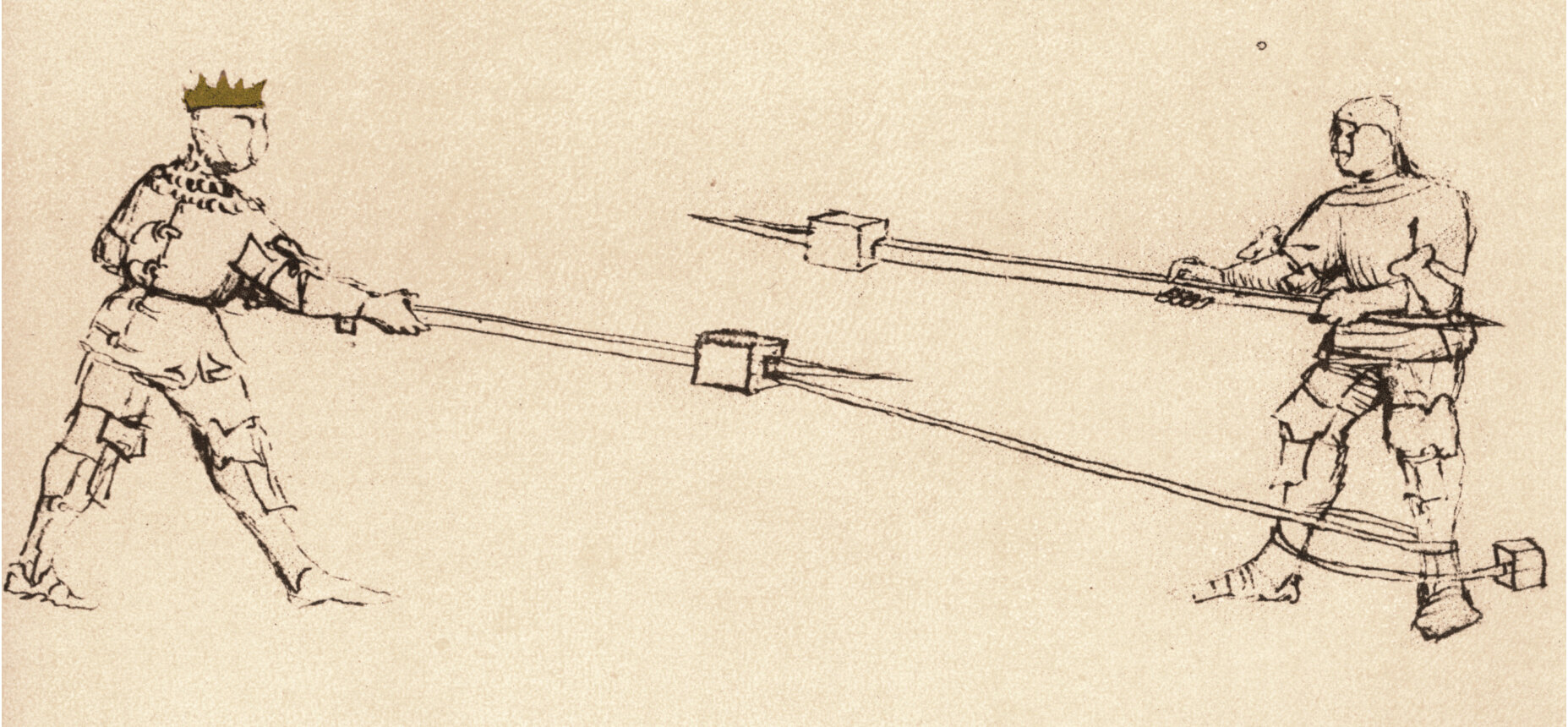

Similar Concepts in Other Cultures

The idea of belaboring someone by using a long length of chain or rope with a weight at the end seems to have arisen in more than one culture and time period. Artistic depictions of such instances occur not only in fictional stories of entertainment but also in actual martial arts manuals.

Above: Italian knights in the early 1400’s utilizing a combination spear and flexible weapon. The author, who describes various weapon techniques in his system of combat, writes: “This play is easy to understand, and you can clearly see how I can drag him to the ground.” [19]

Above: Girard’s 1740 French manual Traite des Armes in which a number of weapon applications are discussed (from spear to grenades). Smallsword techniques are given significant attention and the scenario here instructs its use against the fléaux [flail]. [20]

Above: Woodblock prints of samurai with a kusarigama (鎖鎌 lit. “chain sickle”). One print portrays a chain, the other a rope for the construction of the weapon. Note the meteor hammer-like ball in the upper left corner.

Above: Historic Photographs (late 1800’s early 1900’s ?) and recorded incidents in Japanese history indicate that the kusarigama was actually being practiced with, and not simply relegated to fictional depictions. See sources below for a close-up detail of the photograph on the right. [21]

Above: A popular tale from Japan includes two sisters avenging their father’s death by dueling with his murderer. Versions of the story commonly have one of the sisters training in the kusarigama, eventually ensnaring the opponent’s sword.

Special Thanks

Above: Tea Serpent’s Youtube Page, viewable HERE

Special Thanks to the Tea Serpent Youtube Channel. The channel owner was gracious enough to supply us with roughly one third of the images in this article which were entirely new to us; his comments also supplied clarifying context for some of the scenes depicted. Any mistakes contained in the above article are our own.

Sources

[1] 水浒人物全图 杜堇

[2] The famous book collector, Ma Lian (1893-1935), also had a fragmented copy of this work in the Yi xiang tang edition. Ma Lian and the literary critic Sun Kaidi (1898-1985) both considered this copy a Qing edition, but it is more likely from the Ming dynasty, as the engraver, Huang Chengzhi, lived in the late Ming dynasty. The inscription in the first illustration reads: "Engraved by Huang Chengzhi of Xin'an." The seventh illustration has a similar inscription: "Engraved by Huang Chengzhi." Image and Descriptive Text taken from the Library of Congress’ World Digital Library. https://www.wdl.org/en/item/4455/#languages=zho&institution=library-of-congress

[3] Image of Wu Yong sourced from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts https://collections.mfa.org/objects/202158/wu-yong-the-clever-star-chitasei-goyo-from-the-series-on?ctx=e339535f-7749-4fcd-8bc9-83e1870b8001&idx=0

[4] Images and Text sourced from https://greatmingmilitary.blogspot.com/ Toruidhe Alre has noted “I'm translating 吒 [zha] here as ‘claw.’ It's literally just a phonetic character with no real meaning other than to represent a sound and was often used in transcribing foreign names.

But in this context it's a phonetic transcription of the names of the weapons.

In short it's a character used to represent the sound of the word 爪 [Zhua] ‘Claw’.

In old texts when describing claw type weapons the use of a phonetic character to represent the word claw is more common than actually using the character for claw. I have no idea why this is, but most of the time the character 撾 [Zhua], which means to beat something, is used instead of the 爪 Zhua / Claw character.

[5] Image and Descriptive Text taken from the Library of Congress’ World Digital Library. https://www.wdl.org/en/item/17873/#q=playing+cards&page=2

[6] The 喻子十三種秘書兵衡 (Yu zi shi san zhong mi shu bing heng); see volumes 4 and 5. Images sourced from Harvard Library’s Chinese Rare Book Collection. https://curiosity.lib.harvard.edu/chinese-rare-books/catalog/49-990078924570203941

[7] Shaolin Yibo Zhenchuan (少林衣钵真传), an early Praying Mantis Fist manual which remains largely shrouded in mystery in terms of authorship and being verifiably dated. To read an article on one of the theories in this manual visit: https://theravenswoodacademy.squarespace.com/articles/#/8-hits-8-nonhits

Above: Examples of the various existing copies of Shaolin Yibo Zhenchuan which are all largely uncatalogued, untranslated and have yet to be verifiably dated. To see a version of this manual visit: https://rb.gy/pl1gkm

[8] Text and images sourced from the Art Institute of Chicago. See https://www.artic.edu/artworks/130701/ruan-xiao-er-ritchitaisai-genshoji-from-the-series-one-hundred-and-eight-heroes-of-the-popular-water-margin-tsuzoku-suikoden-goketsu-hyakuhachinin-no-hitori and

[9] Image sourced from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts 通俗水滸伝豪傑百八人之一個 両頭蛇觧珍 at https://collections.mfa.org/objects/209014/xie-zhen-the-twoheaded-snake-ryotoda-kaichin-from-the-s?ctx=c2041489-1ec5-4d75-b8c3-5a1c6e9566bd&idx=41

[10] Woodblock prints sourced from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. These particular prints are unsigned, but pulled from the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Shuihuzhuan (水滸伝百八人之内 挿翅虎雷横 Suikoden hyakuhachinin no uchi). While these specific examples were published in 1853, they originally appeared in 1829 in the book Portraits of Heroes of the Suikoden (Suikoden gazôshû); for the complete book, see 1997.565.1-2 . For the images see: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/464972/lei-heng-the-winged-tiger-soshiko-raio-from-the-series-o?ctx=516f0c80-6025-4175-bf8c-2787a2b5e01e&idx=94 and https://collections.mfa.org/objects/464985/liu-tang-the-redhaired-devil-sekihakki-ryuto-from-the-s?ctx=1eee5ffa-39c1-407f-985b-831f700c616b&idx=107

Above: Written by samurai Arisawa Takesada (有沢武貞 1682-1739), the warrior lists in his book items every samurai should carry when going into battle, including this one: Different kinds of hooks to attach to rope for securing goods and binding prisoners. The rope attached to the iron hook and ring was 2~3.5 meters long. The Shoninki, a ninja manual from 1680, also included amongst it’s list of six essential tools for a ninja the kaginawa (hook and rope). Despite being indispensable for both the samurai and ninja, given how their purposes were described in the period sources these rope and hooks were most likely used strictly for utilitarian purposes and not fighting. 兵器之巻図解 Heiki no Maki Zukai by 有沢武貞 Arisawa Takesada. Retrieved here: https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/2565392?tocOpened=1

[11] By Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) From the Eight Sheets of the 72 Earthly Stars (Chisatsusei shichijûniin, hachimai no uchi), Sheet 10 of 12 (Jûnimai no uchi jû), from the series One Hundred and Eight Heroes of the Shuihuzhuan (Suikoden gôketsu hyakuhachinin) [水滸伝豪傑百八人 地煞星七十二員八枚之内 十二枚之内十] For complete image, see: https://collections.mfa.org/objects/530273/from-the-eight-sheets-of-the-72-earthly-stars-chisatsusei-s?ctx=c69c9e94-c34c-4df1-9497-c7d9d53a76be&idx=4

[12] Variations of these illustrated figures wielding the flexible weapons can be found in books and scrolls such as 水浒百八人画像临本.陸謙筆 and 天罡地煞图.陆谦画.多胡真祇模. See for example: http://gmzm.org/gudaizihua/shuihurenwu/index.asp?page=9

[13] These paintings were first brought to our attention by https://www.antiquechinesesword.com/meteor-hammer. Check out their blog for photographs of antique meteor hammers.

[14] Rare photograph supplied by Alexander Tse. Biographical information from Wan Laisheng's Wushu Huizhong, translated and supplied at http://www.naturalstylekungfu.com/lineage.html Should anyone posses a better-quality image of Zhao Xin Zhou practicing meteor hammers, please e-mail theravenswoodacademy@gmail.com

[15] https://www.antiquechinesesword.com/long-chain-whip

[16] retrieved from: https://xianxiao.ssap.com.cn/pic/detail/id/1569293.html?fbclid=IwAR3L4tlt5P20xyN6Tei0cf_W8xpIfxmCw5taNyA6bWOuf14JmVv8-corEks

[17] Image of Dai Zong the Magical Courier from https://collections.mfa.org/objects/260020/dai-zong-the-magical-courier-shinkotaiho-taiso-from-the?ctx=cca4419d-617a-4096-a53e-921dd2848ff3&idx=135

[18] “As of 2016 there were only three remaining teachers of the traditional fire meteor spinning in Sandun, all of whom were very advanced in years. Recently the Sandun Township Culture Station has started a project to preserve the tradition. This includes collecting historical information and artifacts of the local fire meteor tradition, interviewing the last few remaining masters, producing a video featuring interviews and demonstrations, working with the masters to do a series of fire meteor demonstrations in public and at the local schools, and starting classes at the local culture station.” Image and all text concerning Fire Meteor Hammers taken from Tea Serpent’s youtube channel, from the video available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dAkA5a7Fj2w

[19] https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Fiore_de'i_Liberi

[20] Girard’s treatise accessed through google books: https://books.google.de/books?id=3EdfAAAAcAAJ&hl=de&pg=PT8#v=onepage&q&f=false

[21] Pictures of kendo practitioners sourced from https://togetter.com/li/1464777 and https://twitter.com/shinjisumaru/status/1224713422836846592

Image Detail: Note the wrapped cord around the bamboo sword and the dangling weighted end.

This Article was first published March, 2021.

![Above: Detail from a group setting with a man armed not only with a meteor hammer, but also with a sword and spear. [11]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c1bd8403596ec73f1a54c6/1615846223992-3R22F6QKK15MUO11V6MX/SC229886+copy.jpg)

![Above Left: Yet another protagonist from the Water Margin. Above Right: Examples of an entirely different flexible weapon from an old military encyclopedia. [17]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57c1bd8403596ec73f1a54c6/1615856434647-I9LJ78TJ6JJ7U7161OVQ/New+Project+copy+7.jpg)